4) Passive Investor Due-Dilligence Part 2: Numbers

Investing as a LP requires High Level due-dilligence

What is the Internal Rate of Return (IRR)

IRR is the most used calculation in private equity real estate investments, but what exactly is IRR?

The IRR (internal rate of return) is a time-weighted return metric that is common in both financial accounting and real estate investing, where the time value of money and liquidity risk are major factors in investment decisions. IRR represents how long it will take for your money to be returned over time and it shows how hard your money is working.

IRR vs ROI

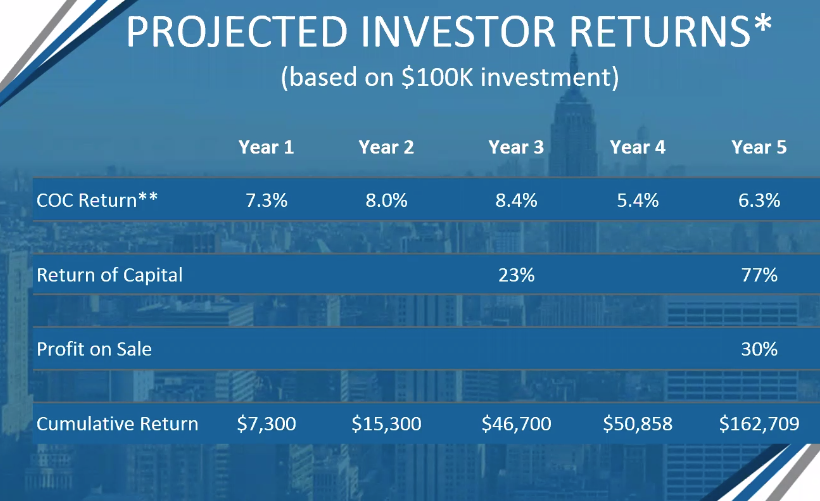

IRR can get mixed up with return on investment (ROI), the difference can be best explained with an example. If you invested $100,000 into a syndication and received $300,000 in return, you would likely think that’s a good investment since it’s a 300% return on investment (ROI).

However, if it took 20 years to get $300,000 then that would be a 5.65% compound annualized return (IRR). This is the main flaw of ROI – it doesn’t account for the time period that it takes for you to receive distributions.

To see the difference in person between a B vs C class location and asset cannot be replaced… but once you do you never have to do that again! 😁 We recommend investors come out on at least one property tour to see the assets and meet the people. That said most busy LPs will not come out to visit the properties which is why this numbers section is so critical.

Comparing IRR Between Investments

IRR is not always useful as an apples-to-apples comparison between two equity investments. If two equity investments have two different target hold periods and different business plans, IRR may not be a useful device for assessing which is the more appealing investment. Combine this is two different assets/business plans with different tax implications and you can see where it makes comparing two investments very difficult.

Take the example of two hypothetical realized investments:

Value-add Investment

A common equity investment into a value-add redevelopment and repositioning of a Class C multifamily property.

The Sponsor expects to execute an aggressive project improvement plan, bring rent rolls positive, and exit through sale after a 3-year hold.

The Sponsor expects to earn the vast majority of profits through exit, and ultimately hopes to achieve a project-level IRR that would result in a net 20% IRR to LP investors on the project.

Stabilized Assets

A portfolio of mixed assets, primarily in gateway markets, stabilized (defined as 90% occupied or more in multifamily apartments), and yielding present cash flow.

The manager of the portfolio expects to achieve cash flow and make distributions throughout the term of the project amounting to an annual average of 9% per year across a 10-year holding period with a modest exit resulting in a net 10% IRR to LP investors.

What is a good IRR:

IRR is a calculation that can be manipulated by whomever does the calculation (mostly around what return a person can continually get with the cash flow they get off the property). Moving the refi or sale up a year can bump the IRR up 20-30%!

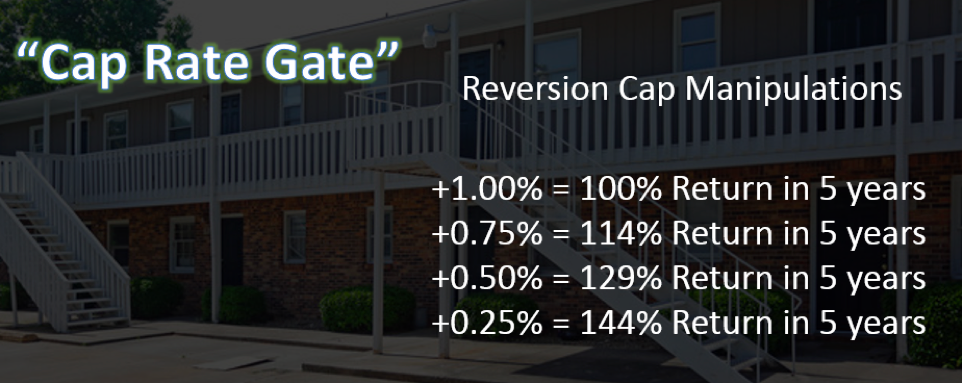

It used to be 100% in 5 years was the gold standard. But as deals got harder to find, 80-100% total return in 2020s seems to be the gold standard – which includes cashflow at high single digits. Of course this can be manipulated greatly based on assumptions (which you are going to learn a lot about in this module). This is your job as a LP to determine if the right assumptions are used (see “Cap Rate Gate” below), but I don’t really look at the IRR because it’s highly manipulated by sneaky syndicators. I personally look at the total return over the 5-6 year period and focus on the assumption that were used to get that proforma 5 year return:

Major Factors in the proforma return:

- Cap Rate to Reversion Cap delta (ideally 0.5-1.0% increase)

- Assumed rent increases per year (ideally 0.0-2.5% increase per year)

- Assumed full occupancy (ideally less than 95% not including economic vacancy)

- Ability to bump the rents (This is the most difficult for LPs to verify)

What else do you look at?

Return = Cashflow + Appreciation (Market Appreciation + Forced Appreciation)

A lot of the stabilized deals with some value-add I go into have the total return made up of about 50% cashflow (during the hold period) and 50% appreciation (paid at exit) where half of all the gains are paid out during the life of the hold (typically quarterly) due to cashflow and the other half of the gains are paid out at the sale or exit of the property due to forced appreciation.

A development project or heavy value add which is a minority part of my portfolio will likely have 0% coming from cashflow and 100% coming from the sale or exit of the property. Everyone has their own criteria on what they are looking for. It is important to know what you are looking for but know that no one deal is going to hit you investment target perfectly and your job as to acquire dozens of these deals that get your weighted average where you want to be.

What is Forced Appreciation

Market Appreciation is getting lucky. Its when you buy an asset and it magically goes up in price… similar to when you hear they story of someone buying a house in the Bay Area for 600k and it is worth 850k soon after. Its based on luck or good picking but essentially we see this as “easy come, easy go”.

The other side of the appreciation where we focus on is Forced Appreciation because we have control over this side and often times we can execute in good and bad times (independent on what is going on in the world).

Forced appreciation occurs in multifamily assets when you increase the income and/or decrease the expenses. The more Net Operating Income (NOI) a multifamily asset produces the higher the price of the asset itself.

In practical terms we “force” this appreciation by increasing the rents for each unit. Generally speaking, we do this by:

- Rebranding the property and aggressively marketing it

- Extensively renovating the exterior of the property

- Landscaping

- Painting

- Building facades

- Etc

- Renovating or adding common areas

- Lounges

- Dog parks

- BBQ areas

- Pools

- Etc

- Renovating the individual units themselves

- Adding washers, dryers, and dishwashers

- Partnering with brokers who secure high paying tenants

- Much more…

On the expenses side of the balance sheet we reduce costs by:

- Implementing a strategic preventative maintenance plan

- Renegotiating maintenance contracts

- Going green

- Installing “low flow” toilets and sinks

- Replacing light bulbs with LED bulbs

- Updating old “power hungry” appliances

- Much more…

Market Appreciation is Luck… but Luck = Opportunity + Preparation

What is “Market Appreciation” and how do we capitalize on it?

Market appreciation occurs when demand increases for properties in a certain market. This causes the price of all properties in the market to increase in price. It’s no secret that many real estate markets in the country have dramatically increased in price on just the supply vs demand because we tend to invest in asset classes (like workforce housing) that have a supply shortage, and in better markets (and in even better sub-markets) – the concept of buying in emerging markets.

There are many factors that drive market appreciation, below is a list of some of the major factors:

- Population growth

- Job growth

- Demographics

- Interest rates

- Desirability of the market itself

- Much more…

By investing in a market that is growing, and projected to continue to grow, investors can reap the benefits of this overall market appreciation as their individual properties rise in price in line with the overall market.

We target highly specific markets that we identify as major growth markets. These markets are growing and the fundamental drivers of that growth are strong. For example, take Huntsville, Alabama as a “market”. We also drill down into the sub-markets which are higher in growth to the market average.

The Cost to Syndicate a Real Estate Deal

Now that we’ve gotten past the “what is a syndication in real estate” part of the course, we can get into the costs and money aspect.

The first logical question is about the cost of a syndication.

There are several major fixed cost items that every syndication requires, including: Real estate contract attorney, SEC attorney, earnest money deposit, diligence, preparation of private placement memorandum and SEC filings, loan application fees, and more.

So, let’s break them down. As some fees are percentage based, I’m going to create a hypothetical $2,000,000 deal.

- Attorney for Purchase Contract - $3,000

- SEC Attorney for PPM – $12,000

- Earnest money deposit – 1% – $40,000

- Diligence – $25-$50 per door – $4,000

- Loan Application – 1% – $40,000

- Other Financing Costs – 0.5% – 1% – $20,000

Total Costs – $119,000 to get the deal done, of which $40,000 goes toward the purchase.

So the total fixed costs are $79,000 or 2-5% of the total deal price. As you can see, this is not cheap!

The syndicator has to front all of the money and if the deal doesn’t close, most of that money can be lost. So, you can see one reason why syndicators are compensated pretty well.

And you can also see why some unscrupulous syndicators might manipulate the numbers to sell a deal that might not be so great – they’ve already put some skin in the game.

How Does A Syndicator Make Money?

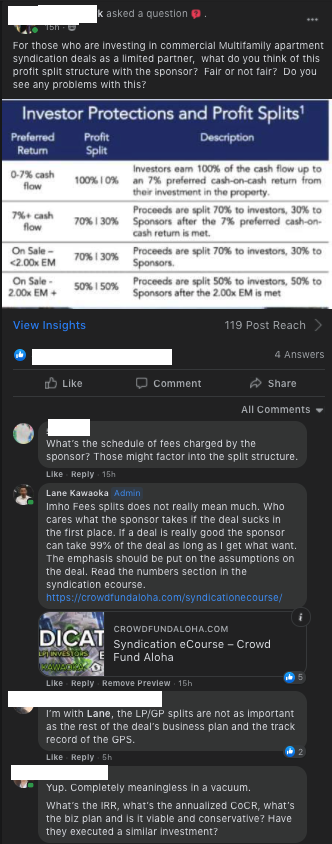

Your Sponsor is not going through the labor of finding good deals, operating it, putting their name on the loan, and all the issues/liability that comes with taking on passive investors (with their own personalities) for free.

Syndicators typically earn between 25% and 50% of distributable cash (carried interest) generated from operations, refinance, or sale of a property, which may be paid as a direct split between the members and the syndicator (i.e., 70/30) after the preferred return if there is one.

Fees. Fees are an expense of the syndication and may be collected by the syndicator on a monthly, quarterly or annual basis. The typical fees a syndicator may earn are shown below:

Financial planners and the Wall Street Industry has been known to take the majority of returns often with no skin in the game or carried interest.

Check out some of the hidden fees in more traditional assets.

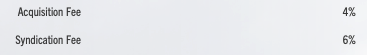

What Type of Fees Paid to Syndicators?

The above fees can be broken down in the three main fees (so you might have to combine some of the above fees under one of the categories below):

- Acquisition fee (paid % of the asset price) – normally 1-3%

- Asset management (paid % of the income the asset produces) – normally 1-3%

- Distribution or exit fee (paid % of the sold asset price) – normally 1-3%

- Development fees (this is present in development deals) – example

NOTE: Just because these fees are high or the split structure has too much going to the GP does not disqualify it. This is what unsophisticated investors think who have a surface level of understanding of these deals. Again its all in how much meat there is on a deal. For example, our process on setting fees and splits is to underwrite conservatively for LPs to get 80-100% ROI on their money in 5 years. If the deal is very fat due to our deal finding ability…we will bump up our fees. Hopefully you are starting to see these investments as products and they have a set market price. Your job is to determine if under the hood of these packages is it is underwrote properly and with a good sponsor.

If you have not yet please review at least a couple of past deal webinars. This way you have some basis in reality of what deals look like and the academics you are learning in this ecourse come alive!

Real Estate Brokerage Fees. A syndicator who is a licensed real estate broker or agent in the state where the property is located may also earn commissions or fees for providing licensed brokerage activities to the syndication, including:

- Commissions on purchase of the property

- Resale commissions

- Property management fees (if the sponsor team does not live nearby the asset and hires a 3rd party property management company). On your 1-8 unit you might be paying 8-10% of rents but commercial property manager compensation plans are different. Normal ranges are 3-6% with some fixed salary costs for staff.

Expense Reimbursement In addition to the above fees and distributions a syndicator may earn, the syndicator can get reimbursed for payments it makes to third parties during organization of the company, due diligence/acquisition or operation of the property. Sometimes if a property is off market the sponsors might pay a finders fee to the wholesaler who found the deal (range 1-3%)

Understanding the GPs fees will tell you what their incentives are and how they operate. Don’t always choose the sponsors with the lowest fees. Sometimes high fees are just the cost of doing business when they generate great returns for you.

How are Investors Paid in Syndications

Preferred Returns

Preferred returns (“Prefs”) are utilized in some deals and refer to the threshold where profit sharing between the investor and sponsor begins. This can also be called a hurdle. Investors receive 100% of the distributable cash flow until this threshold (typically 6%-10% preferred return), then above that threshold, the sponsor receives some of the distributable cash flow.

The distributable cash flow is the gross revenues minus expenses, debt service, and fees.

The preferred return creates an incentive for the sponsor to do their job well. If the deal does go south, it’s the investor that takes the risk. So to correct for that, when the sponsor also puts his/her own capital in the deal, the preferred return “hurdle” gives the sponsor incentive to do everything they can to make sure that project goes well so that they can earn their carried interest split.

The main reason for an operator to not offer the preferred return is because it delays their split of the profits. This his a huge misalignment of interest with the passive investor.

Aside from the lower risk for investors, the fact that the operator is willing to offer a preferred return is a sign of confidence. The operator is essentially saying, “we are so confident in this deal that we are willing to forgo payment until the investors get a good return first.” But be warned, the general partners are the smartest people in the room… when they give a pref they are often taking more of the back end if the deal out preform targets.

Preferred Return Exceptions

True Preferred Return

In a true preferred return (also known as “hard preferred return”), the operator only receives a portion of the profits from the cash flows or sale proceeds after you (the passive investor) receive your entire preferred return.

Preferred Return w/ Operator Catch-up

For a preferred return with catch-up, once the preferred return is achieved, the operator receives all or most of the profits until the operator catches up to the equity split amount to what you (the passive investor) already received from distributions. This type of catch-up provision allows the operator to receive it’s entire equity split as originally agreed by you.

Return of Investor Capital

Most syndications have a dwindling principal, if the principal is paid down through payments above the preferred threshold/triggers (i.e. refinance or supplemental loan, when the deal hits 80% ROI or over a 15% IRR), then the preferred return would be calculated as a percentage of that lower principal. Some operators will say that this is a good idea, so you’re not paying taxes on the cash flows. However, your preferred returns start to diminish and the depreciation each year should offset all the distributions you receive anyway.

For example, if you had originally invested $100,000 into an offering and in year 3 there was a refinance and you received $40,000, then your preferred return would be a percentage of $60,000.

Distributing Cash to Investors (Waterfalls)

A waterfall refers to the overall distribution of funds and tiers but it is often explains how profits are split after the preferred return (e.g., 70% limited partner and the 30% general partner split).

As an LP I don’t really like these because they are confusing and can be skewed all types of ways. Complexity usually benefits the house (GP) which is why Wall Street tries to make things confusing to un-impower the masses. Ok that might be a little of my opinion but here is what I think about traditional investing.

What if a Deal Goes South (Claw-back Provision)

A provision included in certain real estate partnership agreements, whereby a special distribution tier is included in the equity waterfall that allows for the limited partner (LP) to “claw-back” cash flow previously distributed to the general partner (GP). In the event at the end of the venture the LP has not achieved some preferred return, the GP must give back some or all distributions previously made to the GP until such point that the LP hits its preferred return. This is rare.

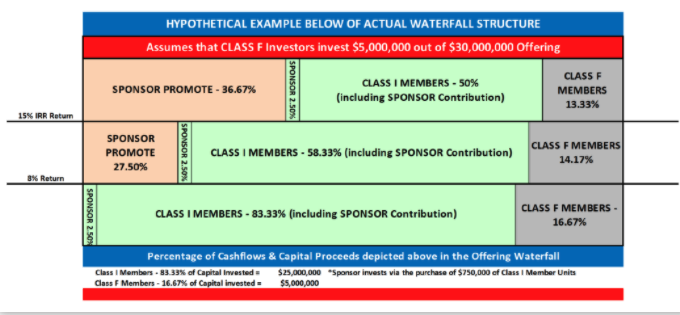

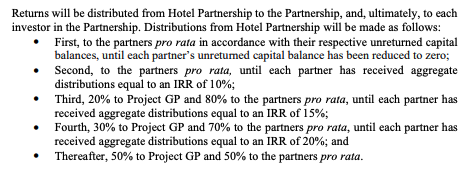

“Waterfall” structure example

With Class B Catch-up

The example below shows an 8% Preferred Return with a 70/30 split and a Class B Catchup Distribution

Let’s say you have a waterfall during property operations that says the following:

- Distributable cash will be split 70/30 between Class A and Class B members respectively in the order below:

- Class A members will be paid all of the distributable cash until they receive a non-compounded, cumulative annualized return of 8% (the preferred return). Determined quarterly and calculated against the Class A Unreturned Capital Contributions.

- Class B will receive an annual, non-compounding, cumulative catch-up distribution of 3.43% (8%/3.43% is equivalent to a 70/30 split).

- Any remaining distributable cash will be split 70/30 between Class A and Class B.

Class B would be entitled to: An annual return of $343,000. However, since there was only $200,000 to pay to Class B in that year; Class B has a deficiency of $143,000 and will be compensated from future cash flow or proceeds from a Capital Transaction (e.g., refinance or disposition of property).

If there are arrearages (deficiencies) for both Class A and B, then the Capital Transaction waterfall compensation with Class B Catchup Distribution would look like this:

- First, repay the Unreturned Capital Contributions of Class A Members; then

- Make up arrearages in Class A Preferred Returns; then

- Make up arrearages in Class B Catchup Distributions; then

- Split any remaining cash 70/30 between Class A and Class B.

Without Class B Catch-up

The example below shows an 8% Preferred Return with a 70/30 split and no Class B Catchup Distribution

Let’s say you have a waterfall during property operations that says the following:

- Distributable cash will be split 70/30 between Class A and Class B members respectively in the order below:

- Class A members will be paid all of the distributable cash until they receive a non-compounded, cumulative annualized return of 8% (the preferred return). Determined quarterly and calculated against the Class A Unreturned Capital Contributions.

- Any remaining distributable cash will be split 70/30 between Class A and Class B.

To show how this works in numbers, let’s assume that Class A had contributed $10 Million and the property generated an annual cash flow return of $1,000,000 (or 10% calculated against the Capital Contributions of Class A Members). In this scenario,

Class A would be entitled to: An annual return of $800,000 ($200,000/quarter), plus 70% of the remaining $200,000, or $140,000; and

Class B would be entitled to: 30% of the remaining $200,000, or $60,000.

Any arrearages (deficiencies) in Class A Preferred Returns will be deferred and made up from future cash flow or proceeds from a Capital Transaction, at the Manager’s option. There is no “catchup” for Class B, so whatever they get in any given year is all they ever get.

The Capital Transaction waterfall without a Class B Catchup Distribution would look like this:

- First, repay the Unreturned Capital Contributions of Class A Members; then

- Make up arrearages in Class A Preferred Returns; then

- Split any remaining cash 70/30 between Class A and Class B.

In the scenario without the Class B catch-up, the sponsor has the risk of paying all distributable cash flow to investors from both property operations and from the capital transaction, leaving little to none for them. This can lead the sponsor to sell it to get their equity back, or keep getting more deals (gaining acquisition fees) and forget about this property.

The best way to make sure interests are aligned is to create a waterfall scenario where the sponsor and investors make money from all phases of property ownership.

In this payout scheme te GP is trying to incentive investors that invest larger amounts

Don’t go chasing waterfalls

[Please stick to the “straight splits” and the “prefs” that you’re used to.]

I like very simple 70/30, 80/20 or 90/10 splits where returns are even and very transparent.

A downside of prefs is when a deal does not perform and it looks like the GP will never beat the pref… well they might dump the deal just because they won’t be able to beat the hurdle (pref) and that might not be in the best interests of the LPs.

*Caveat: you can have a deal where it seems like it is a good pref or high LP split, like a 80/20 LP/GP split but the leads/syndicators can just be taking large acquisition fees and therefore paid before investors anyways.

Investing in Deal with Preferred Returns

Some investors will only invest in deals where there are prefs. This is very nearsighted because:

- Preferred returns have nothing to do with the actual deal (vacancy, business plan, underwriting).

- The GPs are the smartest people in the room and they have engineered the payout scheme to entice investors but extract maximum (but hopefully fair) compensation for themselves. A pref typically is paired with a not so advantageous back end split once the pref or hurdle is reached. So if a deal really gets knocked out of the park, that's when the GP's really win.

Pref’s primary role is for marketing plays (enticing investors to invest). It is not correlated to what kind of a deal it is (development or stabilized).

True Preferred Return Example:

Let’s say Simplepassivecashflow is giving an 8% cumulative true preferred return then a 70/30 split.

Cons of a Pref: Prefs are good for passive investors because it puts them first. But this can also disenfranchise a sponsor if the GP falls too far behind where catching up to the pref becomes impossible. If a sports team is eliminated from making the playoffs, they still play the game but a sponsor might not do the same if they have limited bandwidth where their attention and focus might actually make them money.

Real Talk:

**I’ll be honest here, as a sponsor I don’t like prefs for me and my family because I don’t get paid for my efforts. I do want to make investors happy so if we said we were going to pay out a 8% target return (not a pref) in the first year and we fall a little shirt I might forgo my sponsor cut to make investors whole for that year. That is entirely at my discretion and in the grand scheme of things it is a good business practice and we are in a relationship business where we rely on happy customers coming back and bringing their referrals. Sometimes things happen where it is entirely outside of my control… and maybe we miss our target a bit for a year or two… yes I don’t want to walk away with zero compensation, I don’t think that is fair and everyone signed the paperwork knowing that there was risk involved to not hit projections 100%. At the same time if there was some oversight or I feel investors got a little unlucky with how something ended up I have no problem reaching out of my compensation to make it right because I have honor… its the right thing to do. The last time I checked no one gave me a tip when we 2.X peoples money in 2.5 years (60% ROI per year!).

***As a LP, I never liked prefs or fancy waterfalls because I knew the GPs were always taking a higher cut of the upside to trade off the pref (earlier returns for the GP). I always preferred straight splits where every one was compensated from the the beginning to the last dollar consistently.

Preferred Return Vs Cash Flow

We have covered this previously but wanted to cover from a slightly different angle. Some investors are confused about the implications of preferred returns on cash flow and erroneously believe that an 8% preferred return means that they are expected to receive 8% cash on cash distributions. A preferred return is simply a partnership structure which provides investors a minimum rate of return prior to sharing any profits with the sponsor via a promote. This does not mean that preferred returns stipulate a minimum level of cash flow distribution. Meanwhile, cash on cash return projections are the actual forecasted cash flows.

For example, an investment opportunity could have an 8% preferred return but the average cash on cash over the projected hold period is only 6%. This has become the reality for most deals these days which is why more investors have been bringing up this question about preferred returns and their relation to cash on cash.

Preferred returns don’t imply cash on cash returns so investors seeking to understand an investments cash flow projections should focus on average and yearly cash on cash.

Investor Structure/Split Example

Investor Returns

An alternative structure is a straight split of distributable cash (e.g., 50/50 or 75/25) between the investors and the syndicator.

Debt investors may earn simple, preferred interest on the amount of their investment, while the syndicator and/or equity investors keep the rest.

There is no normal range for deals that warrants a good deal but I have seen deals range from 50/50 to 90/10 splits. 90% going to the LP seems good but that means that 1) the GP is not being compensated much (But Lane who cares) and 2) it signals a thin deal to begin with.

Do not evaluate a deal just by the splits (this is the third time repeating this)… look at the projected returns and check the assumptions which we will get to in the second half of this module.

Now that you understand the basic terminology of how a syndication can split profits and fees, I’d argue the most important takeaway of all is understanding the incentives behind all the splits of profits and fees.

- High Preferred Return and High Fee Deals – This incentivizes the sponsor to close more deals instead of maximize cash flow.

- Waterfall Distribution Based on IRR – Deals with large GP incentive split levels to sponsors once certain IRR%’s are achieved may incentivize the sponsor to find ways to artificially increase the IRR in order to trigger the agreed upon higher GP split waterfall distribution.

- High Returns for Sponsor – The deals that tie the performance of the investment with a large GP split incentive for the sponsor will create more incentive for the sponsor to produce high returns.

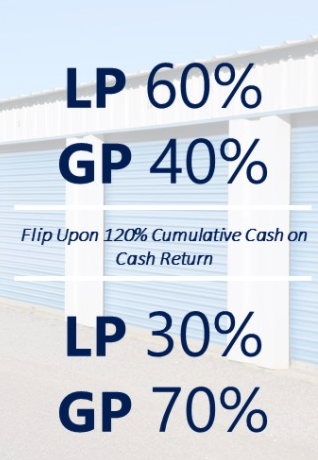

Flipped GP/LP Split (Waterfall/huddle)

See two examples below:

Example 1:

Once investors get their original money back plus 20% the split scheme changes from 70% LP / 30% GP to 50% LP / 50% GP. This is less desirable for LPs but then again the GP needs to be motivated to make money or continue to run the deal with good motivation.

Example 2:

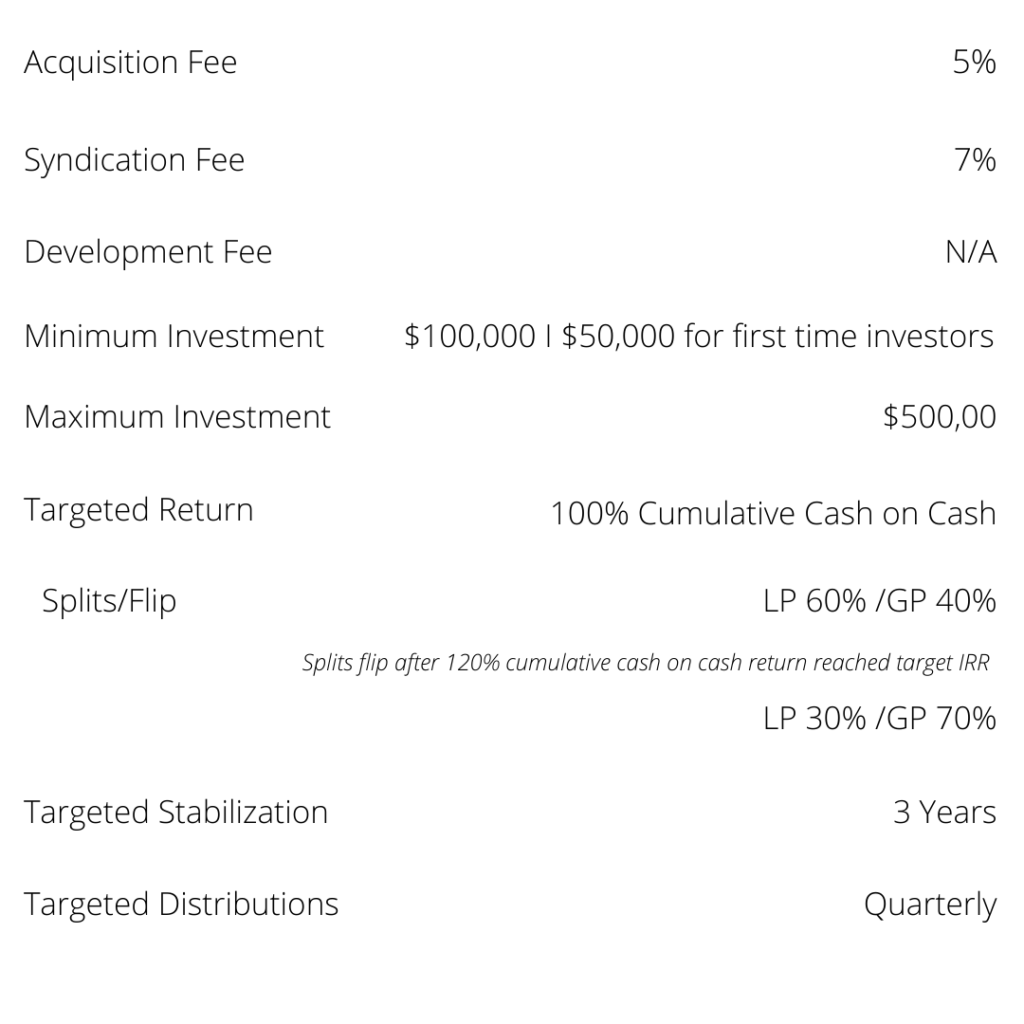

Once investors get their original money back plus 20% the split scheme changes from 60% LP / 40% GP to 30% LP / 70% GP. Again this may not be a dealkiller for a LP. It might be an amazing deal or a more “greedy” money grab for the GP… we don’t know.

That said in this particular deal the total returns was 2x your money in 10 years and the acquisition fee sum was 10% which is 3-4x the average of what I normally see.

See below:

Example 3:

The following is from a hotel deal which can be considered a different set of norms. Instead of a percentage ROI as the trigger for the hurdles, the trigger is at an IRR amount (essentially the same thing).

Hotel deals can potentially be more lucrative (less recession proof than long term rentals). Once can also say that it is more handy work by the operator and thus compensation towards the GP is warranted. Plus there are less operators in this space.

Preferred Return vs Preferred Equity

A preferred return relates to receiving a priority treatment as it relates to the return on your initial capital invested.

By contract, in preferred equity you would be in a priority position in the capital stack to receive your returns during the hold period and in a priority position to receive your initial capital back first when the asset is sold.

In the right financial profile it might be a good idea to diversify your investments in a portion of preferred equity positions to lower the risk profile of your overall portfolio. Remember having 25% of your portfolio making 20% a year is great except the other 75% is lazy equity not making jack in your home, bank account, or stock portfolio. In that situation, brining over a chunk of your 0-5% lazy equity to a pref equity position making 8-12% might really move the needle for you.

The risk is reduced since the preferred equity positions in the capital stack are typically only 10-30% of the overall equity portion of the capital stack. As a preferred equity investor, you would receive your specified return and your initial capital back before any of the other investors. The tradeoff is that your preferred equity returns will be lower and upside limited compared to what you can otherwise get as an LP investor due to the “less risky” position of your preferred equity in the capital stack.

Pref equity means that you also get share of the depreciation!

*Check with your sponsor of course to be sure.

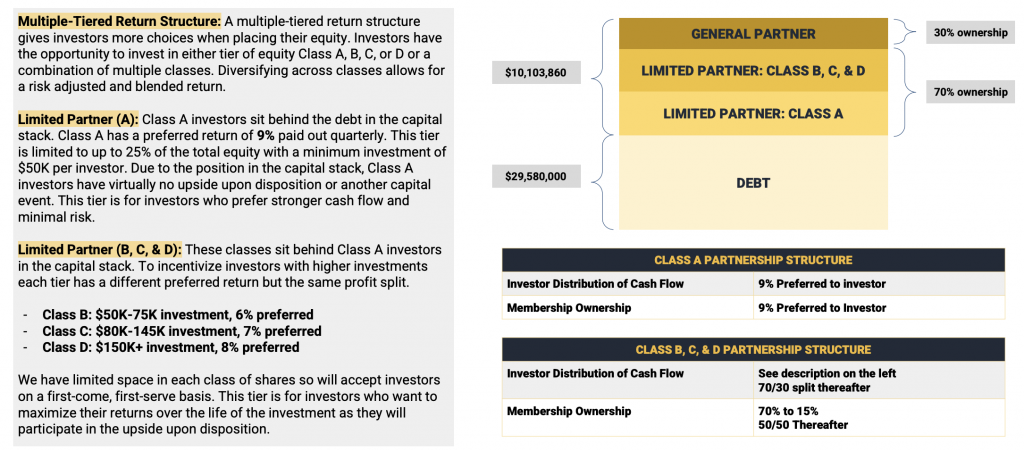

Who is A1 and A2 for? Which one is for me?

We originally had the traditional equity (A2) option when we started to do deals. It was very simple just one option and operated very similarly to most equity based deals out there. Later we realized that a small minority of investors might like the deal (asset/location/business plan) but they might want a more conservative option with a shorter time horizon and not want the upside.

Pref Equity (A2) was born which acts like a debt investment where you get a fixed rate of return with no upside (equity split) but often times get paid first and get to exit first. Every situation is different but this might be ideal for 1) mature investors with higher net worth (over $4m) who just wants to collect a steady income check or 2) new investors looking to move away from ordinary income private money lending or they need to show a skeptic spouse or themself that this alternative asset investing world is real. Or even 3) a hybrid investor that wants to create some piece of mind with a steady income stream (some investors have takes HELOCs or home equity and want to put it to work in a less risky endeavor). I’ve personally done this with AHP… which gave 10% paid monthly. Its not the best returns but I like how it pays my car payment and I admit it just for my personal comfort and not logical. And 4) Some investors who have a glut of lazy equity ($300k+) and really need to get funds moving and potentially get the majority of it back out in a 1-3 years to then roll into a future traditional equity position in another opportunity. See “Pref Equity Timing” section below.

Advance Investor View on Pref Equity

There are times when it makes more sense to take the Traditional Equity (A2) and not the Pref Equity (A1) option.

Think about when you are playing Blackjack… there are some times when it makes more sense to take insurance on a dealer showing an Ace?

It is less advantageous to take the Pref Equity (A1) on deals where the upside is so high because you would be giving that up. Pref Equity (A1) is more appealing when the delta between A1 and Traditional Equity option A2 is not that large of a gap. A deal that might be a better candidate for an A1 position (if you are a A1 type investor in the first place – read section to the left) would be a more “yield” deal or less value add deal like Whispering Oaks or Tara Oaks deal (even if A1 is at 10-11%). I think its a common mistake to get start struck by that 11-12% number… when in the end of the 1-2 years is not much delta. But what is the real difference is the potential for multiple refinances or a 2.5x exit in a few years with A2 Traditional Equity.

By now you should have reviewed least 5-7 past deal webinars. Seeing concepts like bridge loans, pref equity, and different slit schemes comes a live when you see it in a pitch deck or presentation.

We should have began with this at the top but as an investor you need to understand if you are investing as a 1) debt investor (see example video to right), 2) pref equity (paid like a debt investor but get a piece of depreciation/paper losses) or 3) equity (paid on the performance with some sort of a split of profits with GP/LP or waterfall). Confused? Don’t worry it just takes some practice… review old “Past Deal” webinars here.

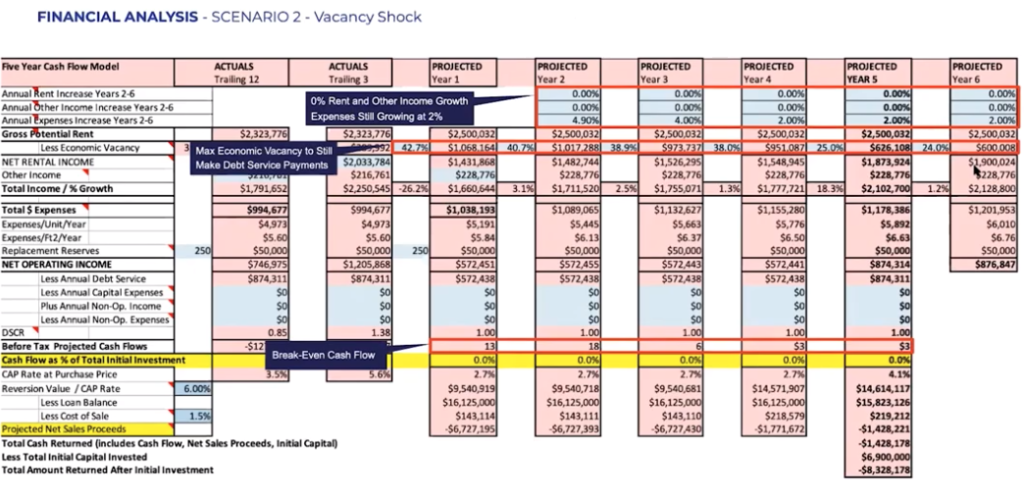

For your practice, here’s a sample of deal analysis. Practice makes perfect!

Past Q&A from older deals regarding Pref Equity (A1):

Just want to be sure I understand how pref equity works?

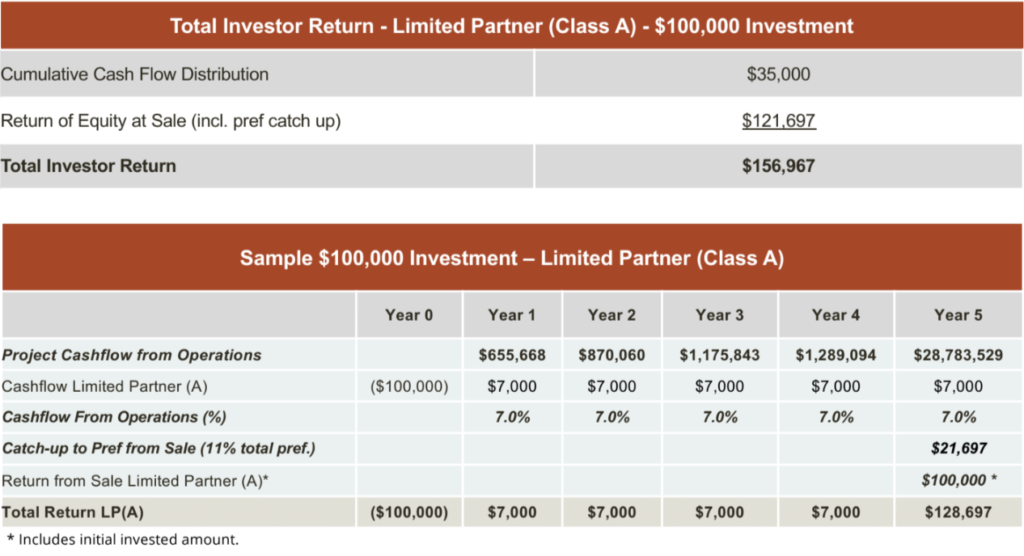

Class A is a “Pure Cashflow” offering. Investors are paid a (in this example) 11% fixed return on their invested capital. When we sell the assets after 3-5 years, Class A doesn’t get to split any of the profits. Again, this class is about “Pure Cashflow”.

Of the 11% cash flow Class A investors receive, 7% of this is paid quarterly throughout the life of the investment (projected to be 3-5 years). The remaining 4% accrues and is paid out as a lump sum upon sale.

See the chart below modeling a $100k investment where we sell at the end of year 5. Of course, 7% of $100k is $7000 and as you can see, our investor is paid $7000 each year, except for year 5 where they are paid $128,697. That final payment is made up of 3 parts:

- The $7000 yearly return

- The “4% catch up”, which has quietly been accruing, totaling $21,697

- And finally, their original $100k capital is also returned

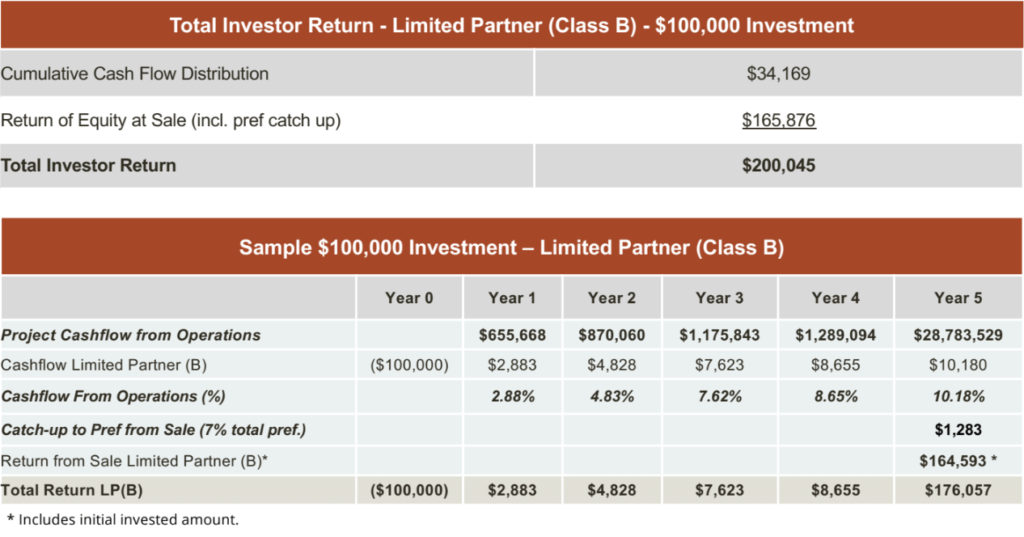

Compare this to the Class B returns table and you’ll notice a few key differences:

- The cash flow each year is variable with Class B. It starts with $2883 in year 1, $4828 in year 2, and then increases each year. Officially, there is a 7% preferred return, but we actually project the average return from cashflow over the 5-year hold to be about 6.8%. Then, upon sale, there is a small “catch up” to cover that remaining 0.2%.

- The total returns are projected to be higher for Class B. Which begs the question, why would someone invest in Class A instead of Class B when the projected returns are higher? That, my friends, is exactly the question we are going to answer today!

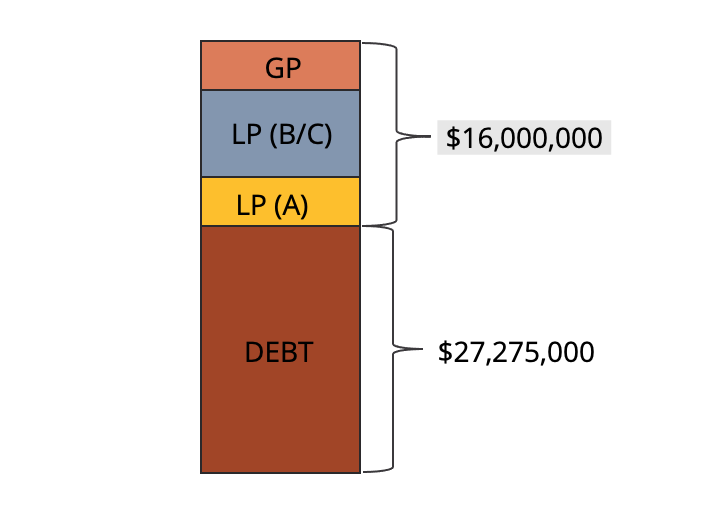

To answer this question, we first need to understand the Capital Stack of a syndicated real estate investment.

See the image here. At the bottom of the stack is the debt, also referred to as the mortgage, or “the bank”. The bank gets paid first, before anyone else, and just like your mortgage at home – if you don’t pay the bank they foreclose and take your house.

Next in line to get paid are the Limited Partners (LP) who invested in Class A. Once they’ve been paid in full, as per the schedule we previously outlined, the next in line is…

The Limited Partners who invested in Class B and Class C. These investors are equal to each other in the stack and they both get paid next.

Finally, there are the General Partners (GP). We’re the last to get paid. In reality, we only expect to make money if (and when) we increase the value of the properties and make a successful exit.

If you’ve made it this far, congratulations… not to offend you… but a lot of this stuff is simple but depending on how you started to understand this stuff I have noticed that a lot of “smart” people can confuse themself more. At this point, I would urge you to get out meet us and real passive investors.

“Why would someone invest in Class A instead of Class B when the projected returns are higher in Class B?”

Safety:

To say it simply – Class A is as close to a guaranteed return as is possible within the investment world.

Now that you understand the capital stack you know that Class A investors get paid before all the other Limited Partners and General Partners. In the event of any unforeseen issues with the project, these investors will be paid first and in full.

Predictability and consistency:

This safe investment option also has stable predictable returns – this predictable quarterly income can be factored into an investor’s financial strategy and household budget.

Simplicity:

Compared with Class B/C, the Class A structure is very simple: Regular quarterly payments at 7% and a final lump sum upon sale catching up to an 11% total. That’s it.

Tax Benefits:

I feel like we’ve saved the best til last. The tax benefit of depreciation will, in most cases, result in the full 7%(+4% on sale) staying in investors’ pockets. In fact, we are projecting that even after this there will be additional depreciation flowing down to Class A investors which they can use to offset additional passive income from other sources! Of course, when it comes to taxes we always have to say, please, speak to your CPA.

When might an investment into Class A make sense for you?

We are going to present several hypothetical scenarios and situations where an investment in Class A may make good financial sense.

- If you are close to, or in, retirement it is widely accepted to be good financial practice to dial back the risk on your portfolio. Move out of growth stocks into blue chips and bonds, don’t invest in risky startups, etc. Investors enjoying their later years should consider allocating some funds to a Class A investment – potentially even across multiple deals and multiple operators.

- Investors who are conservative by nature and have shied away from investing in a real estate syndication may want to reconsider their position now that they know a little more about the reduced risk profile that comes from investing in Class A.

- Many investors (myself included) don’t invest in things they don’t understand. While we have many highly sophisticated investors in our investor base, we also have investors who are new to investing, or highly intelligent and accomplished in their field but not necessarily excellent with math and finances. There is no shame in being early in your financial learning journey. Class A may be a good way to dip your toe, gain some experience with an easy-to-understand investment and continue your financial education.

- Investors who want, or need, consistent and predictable income. For example, an investor with $1mil in liquid capital could invest in Class A and have $70,000 in regular yearly income (when you consider the depreciation tax benefit, this is comparable to earning a 120k+ salary). This income could be used for basic living expenses; food, car payments, entertainment, etc

- Maybe you don’t have $1mil in the bank but you have $100k. Rather than earn 0.06% on your savings (the US average!), you could earn 7% and have $7000 each year to budget towards a family vacation.

- For investors who are overweight with stock exposure, as the market continues to trend south, now could be a great time to cut your losses and cycle some of your capital into tax-advantaged fixed 11% returns.

- Getting a bit more creative, if you had a mortgage with a 5% rate that you were considering paying down with $100k – you could accelerate that paydown by investing that 100k in Class A at 11%, continuing to pay your regular mortgage payments and pocketing the difference between 5% and 11%. Then upon sale in year 3-5 you could pay down your mortgage with the original 100k capital and the additional profits you’ve earned.

We could go on with the examples… But hopefully, if we’ve done our job right, we’ve illustrated the fundamentals of the situation effectively and you can apply the prospect of investing in Class A with your personal situation.

As always, we’re not financial advisors or CPAs and we’ll be the first to say, never take tax or financial advice from an internet mailing list. We’re simply trying to open the door to possibilities you may not have considered so you can have a conversation with your trusted advisors (although they will probably discourage you from participating because they are not able to get a cut of the investment product sales and they are not financial free themselves.

The Dark Side of Prefs

Investors generally like preferred returns because it usually puts the passive investor first. But there can be a dark side of a pref.

Here is the senario, where I have seen other operators quietly play out:

An operator struggles on a deal out the gate or something in permitting hits a snag (in a development deal) where the GP has multiple years of pref to pay out to LPs before they get paid. Ethics aside (putting LPs first) there is little motivation to run the deal because it is effectively a dead dog.

As with most business plans the end goal can be achieved but it might require more time and something where the GP is not motivated to wait for despite being best for the passive LPs. A possible solution (for a smart yet unscrupulous GP) would be to dump the asset prior to realizing the best pricing which would require waiting more time and buried under more years of a pref.

This is why as a LP, I really liked transparent split schemes like 60/40 or 80/20. It is fair for both the GP and LP. And if a pref is going to be used… it should only be used on stabilized cashflowing deals where you can point to the profit and loss statement and allocate the pref return payouts to LPs. Prefs should not be used on development or heavy value add deals. But hey anything goes in this world, and GPs need to throw in prefs to give their LPs a false sense of security.

Differences between Pref-Equity

This is going to confuse you if you do not understand the use of A1 or Preferred equity on the deal. Sometimes you can have one large player take up the entire Pref Equity in a capital stack.

Exiting a Deal – Cap Rates

The Cap Rate is an assessment used by investors to help determine the financial health of an investment.

How to calculate a Property’s Cap Rate

The formula is as follows:

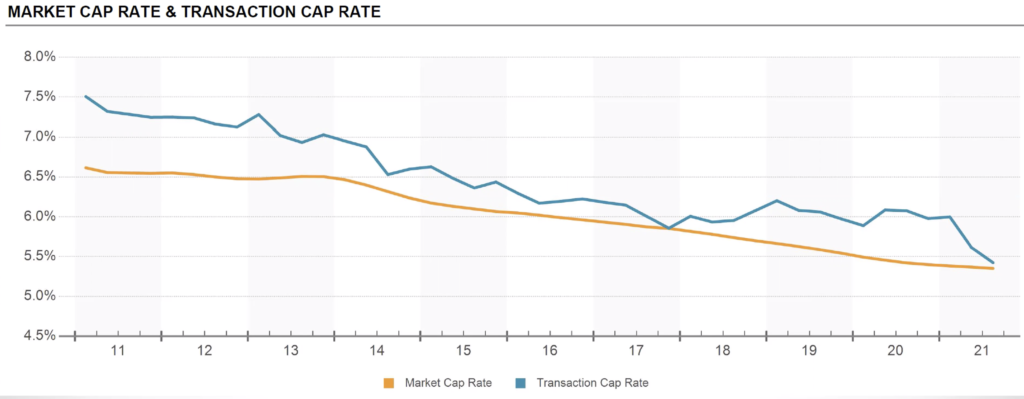

Recently there’s been continual cap rate compression bringing down investor returns. Despite that, we strongly feel that cash flow investing in recession-resistant assets is a prudent strategy rather than having your cash sit on the sidelines as lazy equity.

What Does the Cap Rate Tell You?

Return on Cash Investment

The cap rate helps an investor determine the percentage of return they can anticipate if they purchased the investment property for cash assuming the income and value remain constant.

Investment Comparison

It can also be a useful tool to compare different types of investment properties. For example, if an apartment building is listed for $1,250,000 and has a NOI of $92,500 the cap rate would be 7.4%. Whereas if a mobile home park is listed for $435,000 and is generating a NOI of $37,500, the cap rate is 8.6%. The higher the cap rate the better the return on the investment making the mobile home park a more appealing option – at least at this point in the analysis.

Risk Assessment

The cap rate has a risk/return buried in the rate. If an investor has $1,000,000 to invest, they could place it all in 10-year treasury bond and be guaranteed a 3% return on their investment.

If they purchased an apartment building that generates a $100,000 annually, they would get a 10% return on their investment. The 7% difference reflects the additional risk associated with managing an apartment building compared to the bond investment.

Fannie Mae has different tiers of markets which correlates with the caps of the market. Tier 1 markets like San Francisco, New York, Los Angeles… places we would not invest in because there is no cashflow have the lowest caps (2%-5%). Tertiary markets have higher caps (5%-8%).

What Does the Cap Rate NOT Tell You?

Irregular Income and Expenses

The capitalization rate assumes that the NOI will remain constant. If the property’s net operating income stream is complex – such as with percentage based rent rates – the cap rate will not be able to provide an accurate picture. The more complex Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) analysis will need to be completed.

Additionally, inaccurate income or expenses will dramatically affect the capitalization rate. So you need to verify Profit and Loss Statements.

Cash-on-Cash

A cap rate assumes a cash purchase. Financing will affect the investors ROI. The cap rate will then need to be split between the return on the lender’s investment and that of the investor.

Example: Cap Rate Calculation w/ Financing

- Investor puts 25% down for purchase of an $8.5M property.

- Finances $6,375,000 on a 25 year amortization at 5.05% which creates an annual debt service of $449,448.00

- The lender's return on this property investment (known as the mortgage constant) is 7.1% ($449,448 /$6,375,000)

- The NOI to the investor after the mortgage would be $276,897 creating an investor’s equity return of 13.0% ($276,897 / $2,125,000 down payment). This is also known as the cash-on-cash return.

When weighted based on the loan-to-value/equity position, the cap rate is verified.

- Loan-to-Value 75% x 7.1% mortgage constant = 5.3% lender’s cap rate

- Equity Position at 25% x 13.0% cash-on-cash return = 3.2% investor’s cap rate

- Capitalization Rate (5.3% + 3.2%) = 8.5%

This splitting of the cap rate into the lender’s cap rate and the investor’s cap rate is called the Band of Investment Method. It can be used to back into a purchase price once the lending terms are set and the investors’ desired ROI is known.

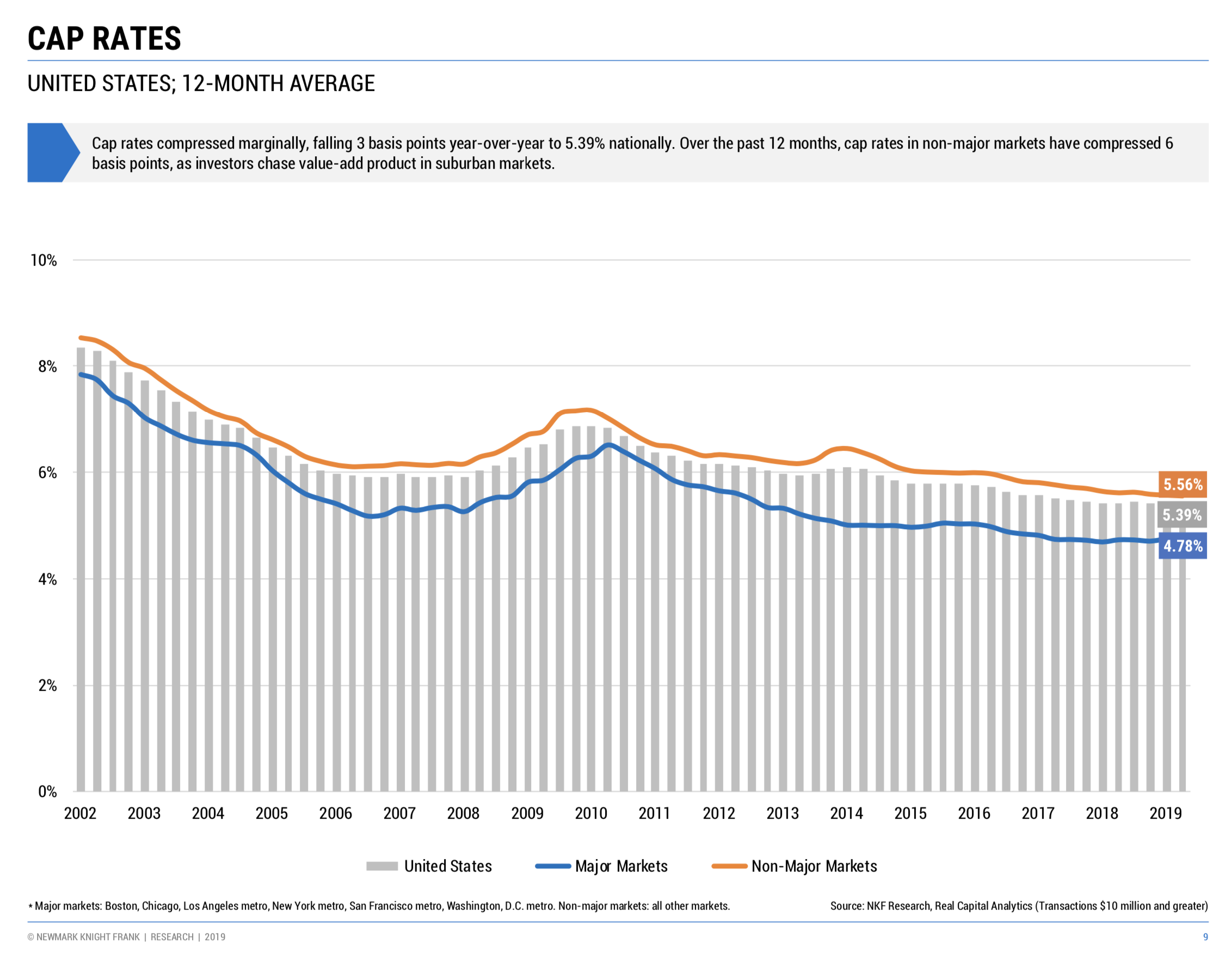

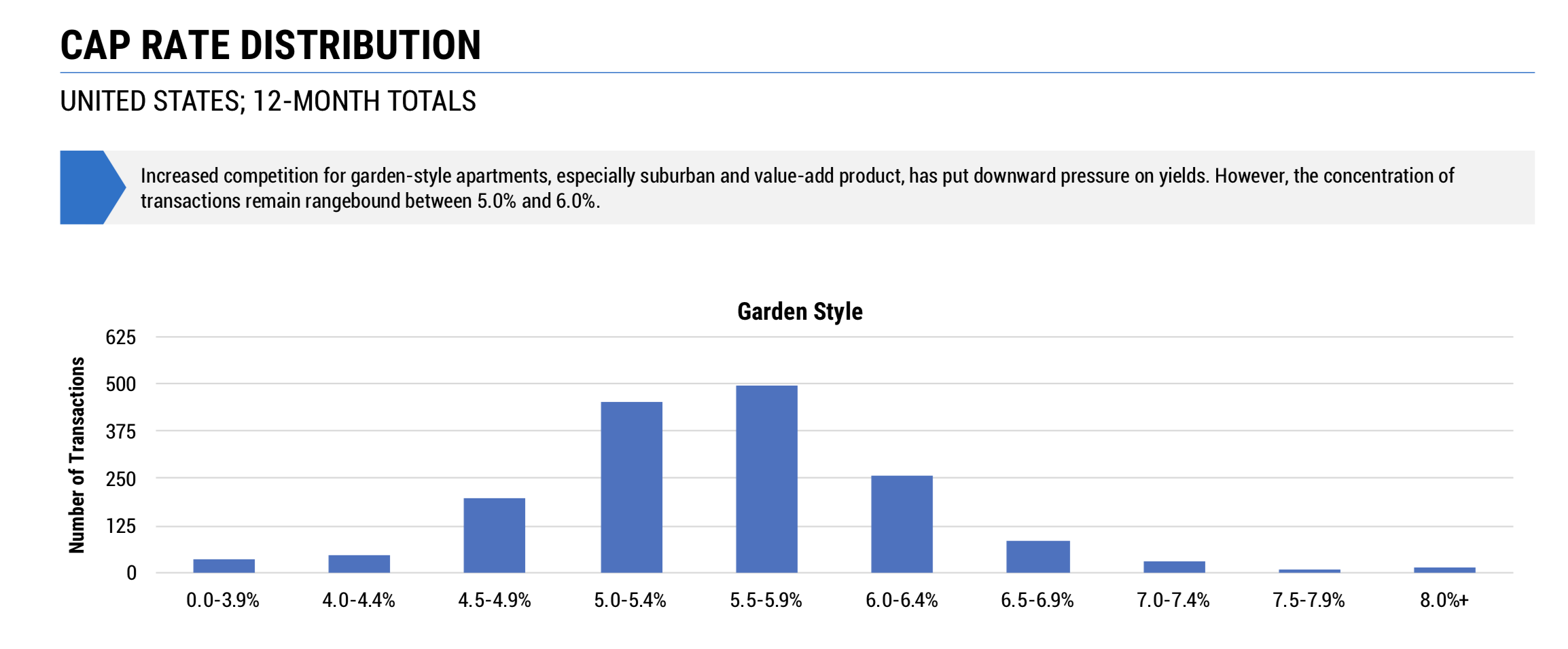

Analyzing Cap Rates for the Best Apartment Type

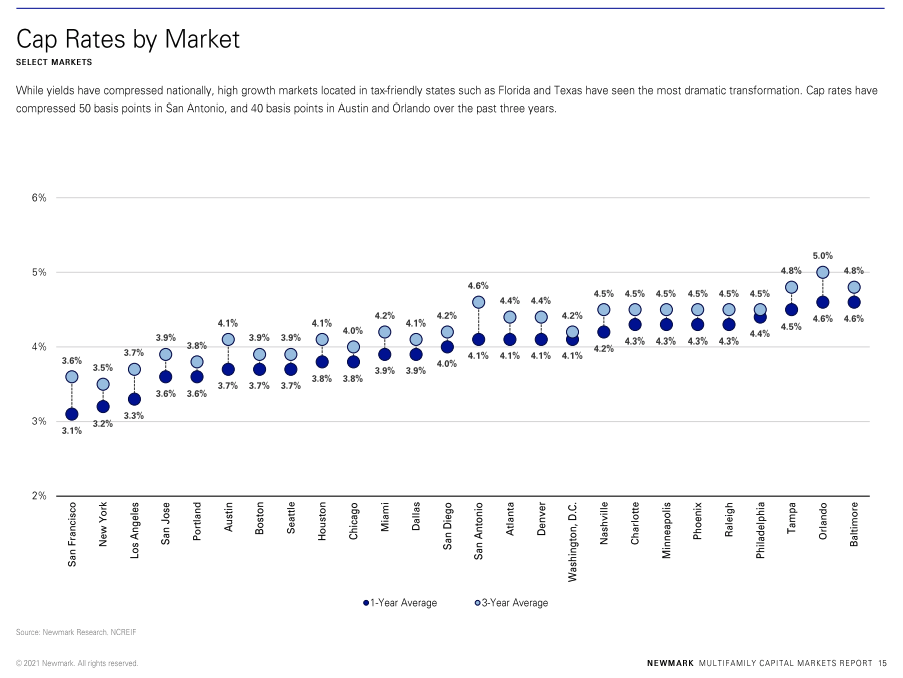

See below graphics for analysis of cap rates in multifamily. Note that these are based on the overall 12 month compressed cap rate.

“Garden-Style” is the 1-3 story Class B or C apartments that many of us like to buy for optimal returns.

When is it a good time to buy?

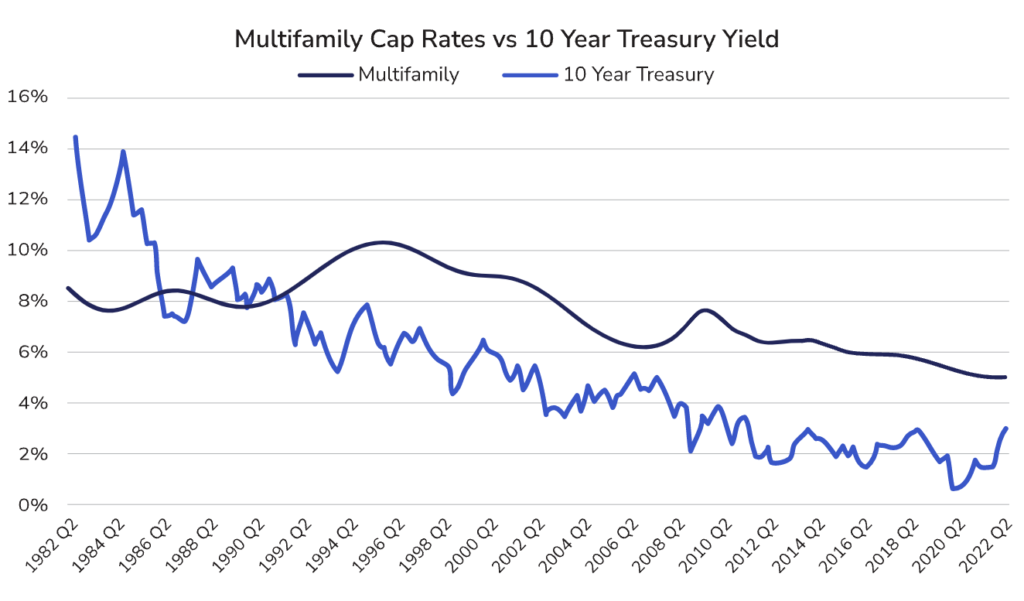

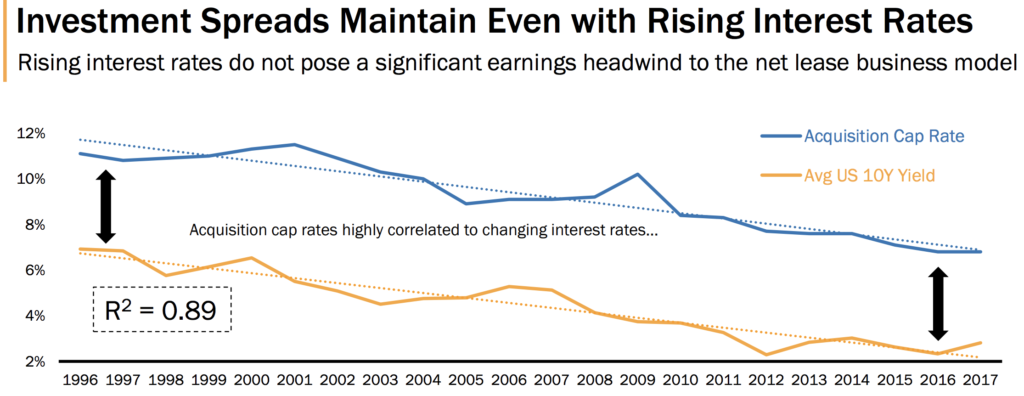

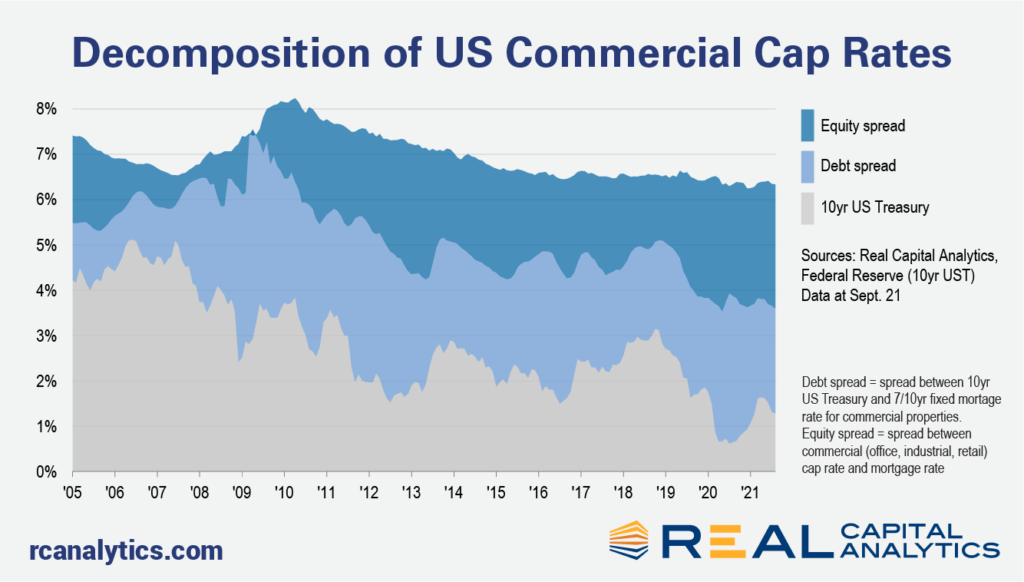

Investors make money on the delta or spread between the cap rate and the interest rate… times the leverage (loan). So as long as there is a spread the investor makes money. Traditionally Cap Rates and Interest rates move as pair. See below which I found as the best academic example for this.

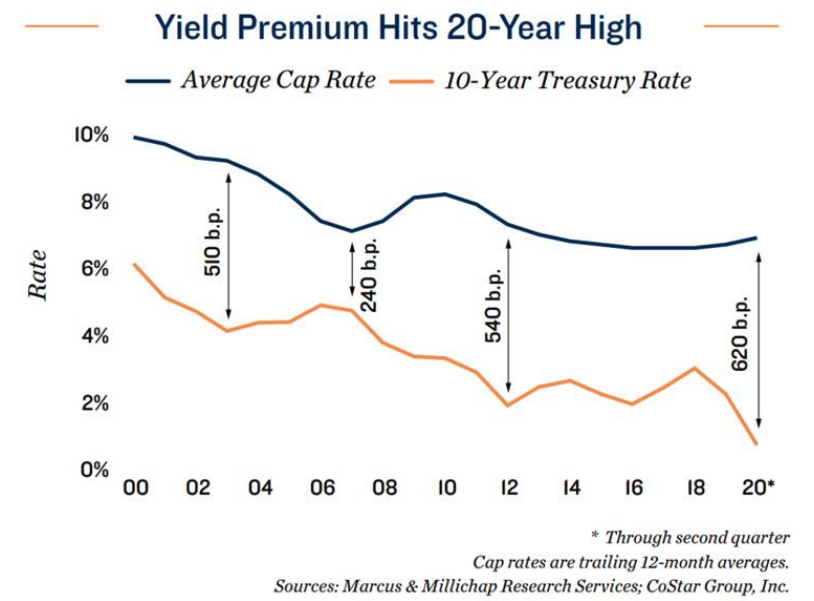

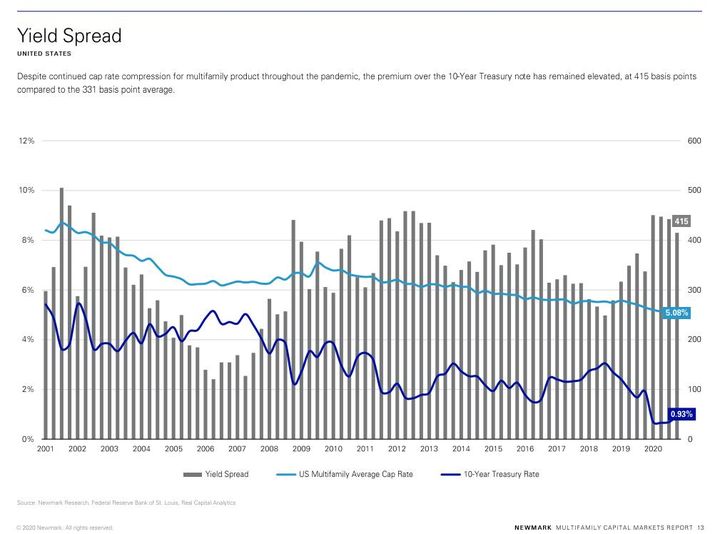

Below is an updated chart which I will try to update from time to time. Note when the spread is small or negative that is the time to take shelter (invest in PEP Fund). But as long as that spread exists investors should see it as a green light from a macro market standpoint. Of course investors and operators should look at each individual deal and market and not this super high level indicator.

Self Storage Cap Rates vs. Interest Rates

Apartment Cap Rates vs. Interest Rates

What are the current/prevailing cap rate of a market so I can compare with the reversion/exit cap rate? Refer to charts like these. Note – there is a large range based on asset class and sub-market within the MSA.

The best time to invest was yesterday!

Commercial vs. Residential market value evaluations

Residential real estate appraisals differ from commercial multifamily appraisals.

Commercial real estate, unlike residential, is appraised using the income method. The more income property brings in, the more it is worth.

The commercial real estate valuation formula is Value = Net Operating Income (NOI) / Capitalization Rate (is also called the prevailing cap for that particular asset/asset class/sub-market). Capitalization Rate (Cap rate) indicates the rate of return that is expected to be generated on a real estate investment property. For example a class B apartment in a great part of Dallas might trade for 4.25% (+/- 0.25) where a class B industrial property in a rough part of Dallas might trade for 6.25% (+/- 0.25). In other words, we don’t have control over this Capitalization Rate as its what assets are trading for (a factor of this number). We have control over the NOI where we increase income or decrease expenses.

Net Operating Income (NOI) equals all revenue from the property (all rents, fees, and other income), minus all reasonably necessary operating expenses.

Cap rates are expressed as percentages and vary from market to market. Within each market, cap rates have a historical range. For example, if a property had $300,000 in NOI and the cap rate in that market was 5%, you’d expect it to be valued at around $10 million ($300,000 / 5% = $6 million).

This Capitalization Rate (Cap rate) often gets mixed up with what the asset is preforming at (the cap rate)… see its confusing. Read on to learn this important concept and don’t be like most unsophisticated Accredited investors that don’t know the difference and just say broad comments like “the caps are shrinking” just to make themself look cool.

"Probably the most important thing in this course"

What is “Cap Rate Gate?”

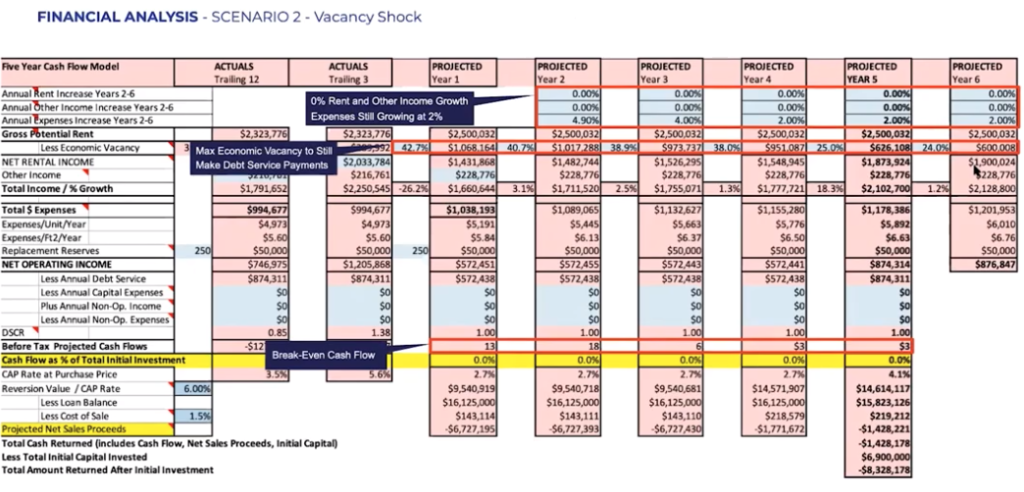

It’s when a syndicator manipulates the reversion cap rate to greatly influence the exit sale price which in turn greatly impacts the total returns, so they can attract investors to a deal.

Typically expenses are always left out or income is inflated which can throw off the cap rate by +/- 2.0. The only true way to determine a subject property cap rate is to get the trailing 12 month Profit and Loss Statement (“T12”) but at that point you have the information to underwrite it fully. Asking for the P&L might be bad form from a passive investors prospective because it might come across as too much information and a sponsor might not want to work with an annoying investor.

The reversion cap rate is a “wild-ass guess” to begin with, but an increasing cap rate means it’s a softer market and you are not going to be paid as much for your NOI. To be a conservative underwriter, you like to see the reversion (exit) cap rate +0.5-1.0% higher than the starting cap rate. By using anything less than +0.75% is simply “kicking the can” down the road hoping the good market continues.

For example if your prevailing (not your starting) Cap Rate for that asset class and market is 6.25% then you want to use 6.75-7.25% as your reversion cap rate.

See below how much it impacts the total return. This is why you need to look under the hood and stop taking the “sticker price” for face value.

Make sure you understand this because this is super important. And it takes a while to understand this as it is a bit counter intuitive. So if you want to be conservative in the future you increase the reversion cap… yes increase. I think people get this confused with what a Cap Rate is of the property and what Cap Rate is used in the market price calculations. Its two different things with the same word.

For example, lets take a class B apartment in 2021 in Dallas might be running well at a 6 Cap. But the prevailing Cap Rates that similar assets are being traded at in that same market would 5.0-5.5 Caps. The 6 Cap again is what the property is running at which is different than the prevailing Cap which is 5.25. In order to do proper underwriting we want to use increase the prevailing Cap (5.25) by 0.5-1.0 to come up with the reversion or exit Cap of 5.75-6.25 to assume for the market to be weaker in the future. A common mistake is to take into account what the current Cap the asset is preforming at which is really an independent number to what the prevailing asset is. If the subject property’s Cap is higher than the prevailing then that’s good, its preforming better than similar assets but if its less it is likely the reason for the discount or sign there is operational inefficiencies. Using less conservative (lower) Exit Cap assumptions will increase the sales price and inflate our total returns.

Question: What is the going cap rate for these types of properties?

How Important are Cap Rates at the Beginning of a Deal?

Cap rates are severely overestimated in most cases from brokers/sellers/syndicators so we don’t really pay much attention to it on the front end of the deal during acquisition. The reasoning is that to get to that number, typically expenses are always left out or income is inflated – so it’s bad data to begin with. Those “above of the line” items are again always manipulated and can throw the calculated cap +/-2.0. The only true way to determine is to get the trailing 12-month Profit and Loss Statement but at that point, you have the information to underwrite it fully.

On class B/C we have been using a 6.5-7.5% reversion cap depending on the market. For example 6.5 in Dallas whereas 7.5 in Gulfport MS. These days nothing is over 7.5% cap (unless it’s a truly off-market deal and a fringe deal under 60-units). I find the current prevailing caps from our operator peers who are apartment operators. Another way is to talk to a broker who has their pulse on the market and knows you need the number for underwriting purposes (and he is not selling you a deal).

In addition. the mere fact that we are doing value add and buying assets that have a management problem (that we can fix) means the property is not performing what it should be.

How I set the Reversion Rate in my underwriting?

If you wanted to manipulate the total return, the one cell on the spreadsheet that is the go to “fudge this cell” or “sharpen the pencil” is the Reversion (Exit) Cap Rate.

You want to see the Reversion (Exit) Cap Rate 0.5%-1.0% higher than the Market Cap Rate. Notice I am using the Market Cap Rate for similar assets (Class A, B, or C) in similar submarkets (locations within the same city), NOT the Subject Property Cap Rate.

On class B/C investments, I have been using 6.5-7.5% reversion cap (2019) depending on market. These days nothing is over 7.5% cap (unless it’s a truly off-market deal and a fringe deal under 60-units).

Exception: Only case where you might do a -0.25 to +0.5 cap rate reversion increase because you are doing medium to heavy value add (15k-50k per unit) therefore taking a B/C class property to an A/B+. More info.

The Subject Property Cap Rate in-place is calculated on the T12, but in underwriting we don’t really take it into account to determine a Reversion (Exit) Cap Rate. Instead, we are going off the prevailing Cap Rate for that class of property in that market.

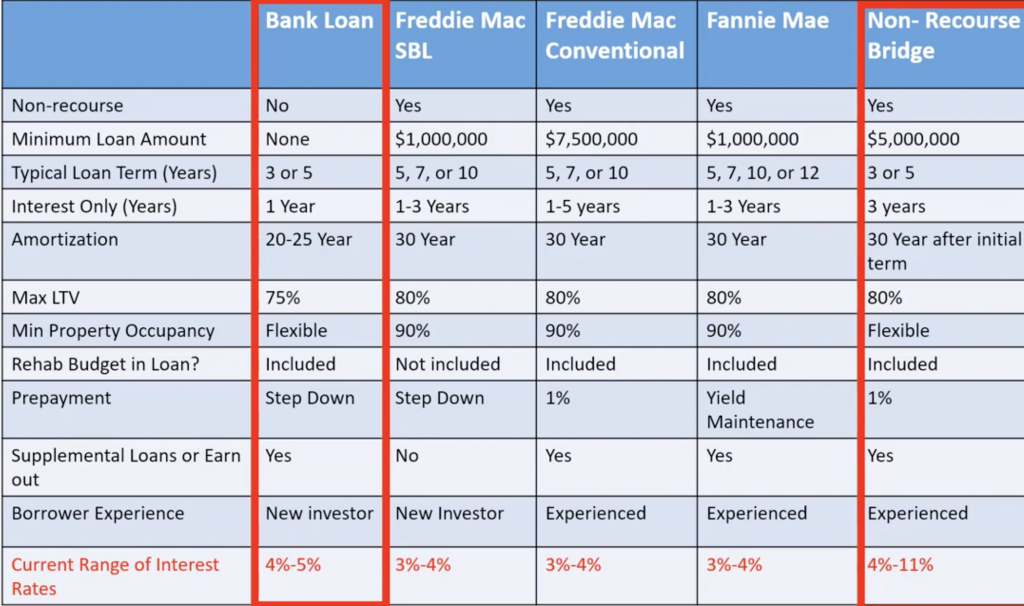

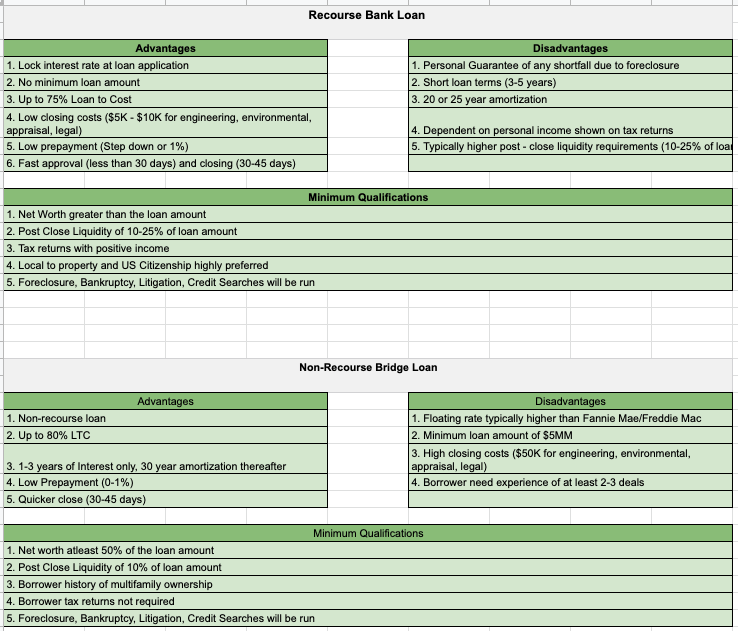

Evaluating the loan terms

Commercial loans are a bit more complicated than your normal residential 30-year amortized fixed rate loan. The major components of the 30-year amortized commercial loan is the rate, term, leverage amount, and pre-payment penalties.

Leverage amount is determined by which market the asset is located in. Fannie Mae/Freddie Mac have lists of tier 1-3 markets; tier 1 markets allow for the most leverage whereas tier 3 are allowed less leverage. Tier 1 markets are mostly primary markets like San Francisco, New York, Seattle, where there are low Cap Rates. Tier 2-3 markets are typically the secondary and tertiary markets that we target due to higher Cap Rates in order to cashflow. Therefore, our loan proceeds or leverage amount is less than that of the tier 1 markets.

Investors will argue that the largest indicator to look at for the stability of the loan is the term. Loans are typically amortized over 30 years with balloon payment at end of the loan term, but the loan might need to be refinanced or reset after the loan term expires. Loan terms range from 3-15 years. The longer the loan term, the more conservative the loan because you are able to have a lot of time to reposition the asset in case the market goes soft and/or interest rates increase. But if you think about it, most times when the market goes soft, interest rates will decrease as the FED will lower rates to stimulate the economy. Either way, you don’t want to be holding on to an expiring loan and forced to make a new loan if you are not ready or in a high rate environment. We like to go into a loan with a term longer than 8 years. So the longer the better… until you take into account some other terms that are correlated to a longer term like prepayment penalties.

Longer is not always better…

Investors usually choose yield maintenance on a 10-year loan because it allows the lender to provide the lowest possible interest rate and highest possible leverage. The trade-off is that investors limit their options. Here are some downsides: yield maintenance has an extremely expensive prepayment penalty, borrowers often find themselves unable to sell or refinance when desired, or borrowers may be forced to sell on an assumption basis (i.e., new buyer assumes existing loan), which usually reduces the price achieved at sale.

I often see projected $0 financing fees upon sale, or exit cap rates that do not account for lower sale price due to loan assumption in a syndicator’s 5-year underwriting analyses. Here are some ways to account for yield maintenance in deals:

-

Underwrite to a 10-year hold

One way to accurately project leveraged IRR in a 10-year loan scenario while also reflecting yield maintenance is to simply underwrite to a 10-year hold. This will conservatively lower IRR expectations (due to time value of money) and also ensure that the sponsor and investors are comfortable with the returns even if they are stuck holding the deal until closer to loan maturity.

-

Raise the exit cap rate

To account for yield maintenance on a 5-year hold, raise the exit cap 25 basis points (bps) (i.e., 0.25%) or calculate the yield maintenance prepayment penalty assuming a sale at 5 years.

-

Use an alternate loan type

Other permanent financing options avoid yield maintenance altogether – loans with shorter terms, more aggressively declining prepayment penalties (step-down), or floating rate loans which offer cheaper prepayment.

-

Value add business plan keeps you out of trouble

Adding value to your investment property is critical to maximize returns and often to protect your downside risk. Instead of worrying about interest rates going up or having to refinance with your note coming due in 1-3 years (oh my!) one can eliminate this P & L risk by increasing the amount of equity by forced appreciation. To use a sports analogy, sometimes the best defense is a good offense (value add) or to keep putting points on the board. In many of our deals, we create a tremendous amount for forced equity month by month that if we can stack a year or two of this progress forward we will find ourselves with six/seven figures of forced appreciation which will make refinancing in even the toughest of times not a problem. If you have the buy-hope-pray model then you need to worry about your loan term being too short and/or your interest rates increasing on you.

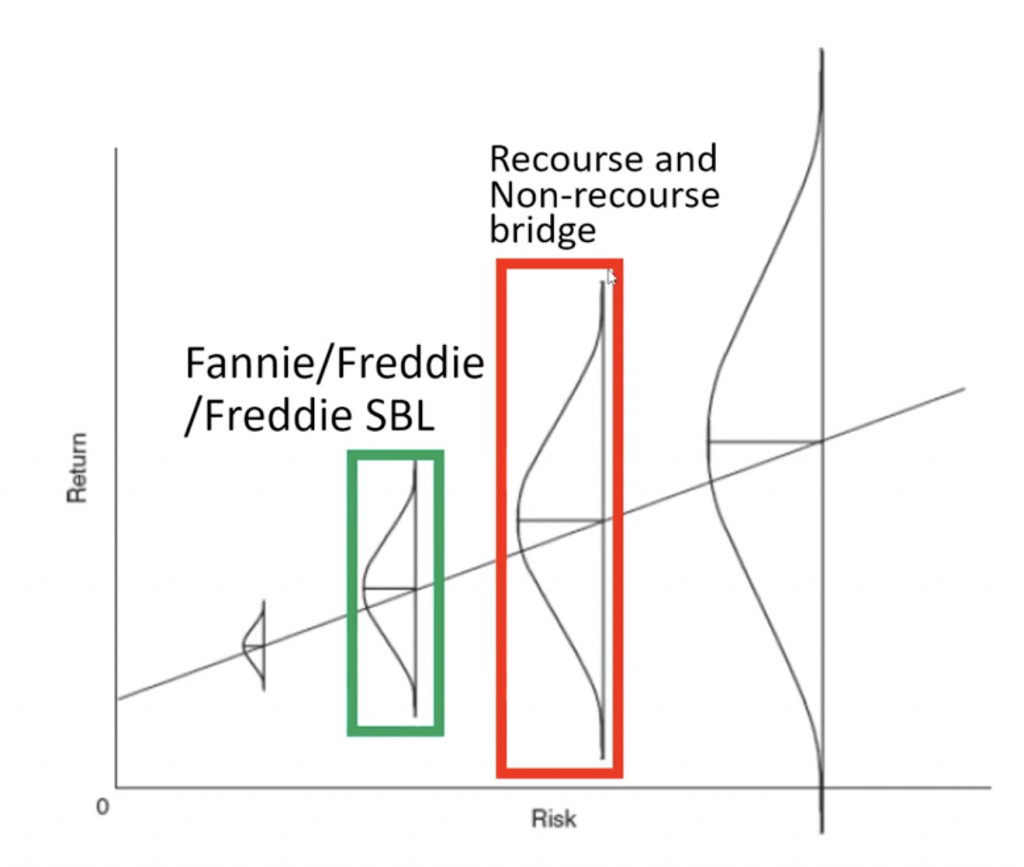

Bridge Loans

Virtually all commercial real estate utilizes debt to enhance returns and improve deal structure. Debt must be conservatively factored into one’s analysis of structuring the best deal for them and equity returns must be evaluated on a risk-adjusted basis. Adjusting returns for risk simply means to evaluate returns within the context of the risk associated with potentially achieving said returns.

Debt is one of the largest factors when it comes to risk, so it is important to understand how the leverage, interest, and term of the proposed debt structure impacts the overall risk of the investment. Higher leverage loans may increase projected returns, but also increase the risk of losing money in a downside scenario. Higher leverage is usually accompanied by a higher interest rate, which negatively impacts cash flow and could put the investment in a negative cash flow scenario if the business plan targets are not achieved. Floating rate debt and fixed rate debt also carry their own respective risk factors. Floating rate debt can negatively impact cash flows if interest rates rise during the ownership of the property. Meanwhile, fixed rate debt can adversely affect a sale since fixed interest rate loans usually have a very strict and expensive prepayment penalty.

Finally, the term, or duration, of the investment’s loan is also a risk factor since a shorter-term loan can create a scenario where the loan becomes due at a time when the property’s value is such that it is unable to obtain new financing to pay off the existing debt. A situation like this can force a sale at the exact worst time, which may cause equity investors to lose some or all their initial investment.

While permanent financing is relatively straightforward, bridge loans demand different underwriting and often have added complexity. In my view, investments financed with a bridge loan should be underwritten to a 3-year hold, since that is usually the loan term. Typically the expectation is to sell or refinance within that period.

A 5-year projection for a bridge loan requires assuming a refinance when the bridge loan matures; however, refinancing creates uncertainty and complication in the model while welcoming a litany of questions from investors. Moreover, I believe it is misleading to call a 3+1+1 bridge loan a “5-year loan” and underwriting to a 5-year hold without including the necessary extension fees in the underwriting model.

Bridge loans are not inherently more risky. But it does magnify a good deal as well as a bad one.

Bridge Loan Test

Although refinances are best avoided in underwriting projections, it is nonetheless critical to perform exit tests and stress the possibility of refinancing out of the bridge loan at maturity. This can be done by stressing the property’s revenue while also raising the exit cap and interest rate to see if the projected take-out loan still has proceeds sufficient to pay off the existing bridge.

Bridge loans are ideal for executing turnaround business plans, but very few deals today actually pass this stringent bridge loan exit test. To avoid this possible downside scenario, investors seeking the flexibility of a bridge loan but are buying properties without high upside, should opt for a lower leverage, lower interest Freddie Mac floating-rate loan (Freddie floater).

Here are some additional nuances which must be considered when analyzing a bridge loan:

- Interest reserves

- Cap Ex reserves

- Replacement reserves

We always assume these reserves are fully spent in the model. Replacement reserves can often be negotiated out of bridge loans (at least for the first year), but it is still wise to factor reserves into terminal NOI to avoid overstating projected sales prices.

Beware: There was a deal that was floating around out there where LP investors thought the deal was going very well. From the LP point of view their were getting their 2% pref every quarter and the monthly reports were very rosey. But underneath the surface the Bridge Loan was underwater and the sponsor group was secretly shopping the deal to get from underneath the loan. Now likely that situation will end fine (because its real estate and things typically end well) but a bridge loan can stress a deal’s financials.

Detailed Analysis Example

[Coach’s comments in ALL-CAPS]

- Address: xyz, KY

- 140 unit apartment complex

- Class B-/C+ built in 1967

- $68k/unit purchase price

- 8% pref, 70/30 split

- 3% acquisition fee [SUPER HIGH]

- 1% asset management fee

- They have their own in-house property management company

- 15.15% IRR, 1.85x multiple over 5 years

- 10% first year rent increase

- 3% market rent increases after first year

- 2.5% Expense Growth YoY

- 6% Vacancy YoY (8% yr 1)

- 4%, 2%, 1% YoY Loss to Lease

- 6.09% entry cap ASK WHAT THE REVERSION CAP… I’D LIKE TO SEE IT 6.75-7.25 for this market

Student Concerns:

- This is only a 1% rent-to-value ratio deal NO BUENO

- They are using 3% market rent increases. That seems normal from my research but just something to think about. 2% FOR THIS MARKET IS BETTER

- They are only estimating an 8% vacancy the first year during a renovation where they raise rents 10%. They aren’t renovating all the units but still seems low. Also the following years only estimate a 6% vacancy. THEY BETTER HAVE 3% ECONOMIC VACANCY IN ADDITION TO THIS

- The price per unit seems high for this class of property, which explains the 1% RV ratio.

- The estimated cash-on-cash is set at 8% (same as pref) but I don’t see how it’s exactly 8% every year. That just seems weird. IT DOES NOT MATTER. IF THE GP CAN’T PRODUCE THEN THEY OWE YOU THE PREF… UNLESS THEY CAN’T AND THEY GO UNDER 😛

How Important Are Interest Rates if They Go Up?

In short, interest rates don’t really matter. It’s a bit counterintuitive because those who do the buy and hold (and pray) model have their spreadsheets and know a 0.5% movement in interest rates can bring your cash flow from 200/month down to 75/month.

This deal is mainly a value add play and we are making more than 3/4ths of our money in equity build-up, not cash flow so that is where the “we don’t care” comes from. And the deals we do this on have a lot of meat on the bone to value add and more than makeup for the carrying costs.

Think of it this way… a house flipper is fine playing 10-16%+ interest rates because he is going to value add the property. The same idea is happening here.

What to Look for When Analyzing Deals

Being a good LP (not over the top one who wastes a lot of time analyzing a deal) requires that you look at the right things. For example:

Rent Increases

You may have to calculate this for yourself as most syndicators will not openly point this out because they might be being too aggressive. 3% here is a very high estimate. We try to use rent escalators of 2% even in strong markets like Dallas or Houston.

Vacancy, Loss to Lease, Expenses

See if you can spot out what does not working in terms of Income, Vacancy, Loss to Lease, or Expenses. The annual rent increases after the first year bump is 2%. This is acceptable for this good market. However, the Vacancy & Loss to Lease (people not paying) is too low. Usually we like to see a Vacancy of 5-10% depending on the market, with 10-15% in the first year as we kick out bad tenants. The Loss to Lease (or deadbeats not paying) is typically 2-5% with a surge of 3-8% in the first year. Expenses at a bit over $4,000/unit is good.

Cash-out Refi

A cash out refi is part of the above pro forma in year 3 in order to come up with the total return. A refinance is a big "if." I would rather see how the property preforms without a refinance event and just a straight sale.

Break Even Point

The biggest risk in all real estate deals is keeping it occupied (or economic occupancy - people actually paying). One way of determining this is asking what the break even point is. Be careful that this stat can be manipulated and you as the investor need to be sophisticated enough to ask the right question (or fall victim to "syndicator rope-a-dope") - for example if you asking for occupancy (w/ assumed 3% economic vacancy) or economic occupancy with economic vacancy accounted for? Also is rent increases included... now this can start to get very difficult to pin down a sponsor for a real number but its a start and at least you are aware of these games. We don't like to assume that the "full occupancy" will be greater than 92-95% occupied (especially in the first year) plus the assumption that ~3% of those tenants will not pay therefore bringing max economic occupancy down to 89-82% economic occupancy. PS - reversion cap (6%) looks really conservative however this deal is near Waco Tx (smaller tertiary/"turd"tiary 💩 market) where reversion caps should be much higher than solid secondary and tertiary markets

Check Your Numbers

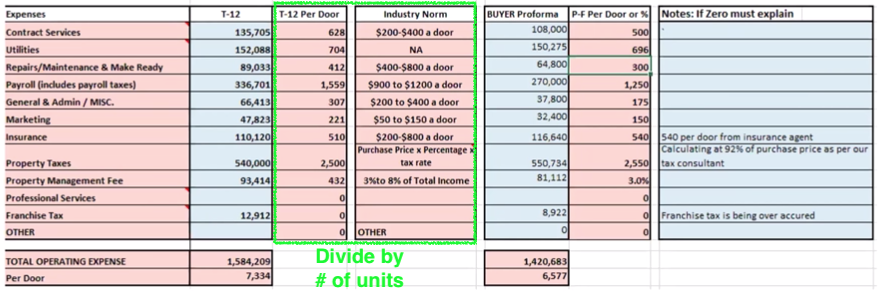

Here are some rule of thumbs on the Profit & Loss statement

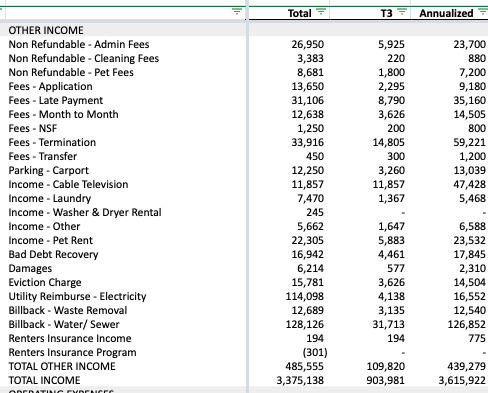

What’s other income?

All the other income the property makes other than rents. See above an example from a 240-unit Class B+ asset.

Note: The following analysis is out of the scope of most LP’s due-dilligence. It would definitely be unusual for an LP to ask for breakouts of the following.

For our large apartment complexes, we typically have 20-30 days (all during helping investors sign their PPMs and facilitating wires) to conduct an exhaustive review of all the moving pieces related to this business and asset we are looking to buy.

While those teams are busy getting in all the units, we are executing a file audit making sure the paper copies match up with what is listed online. During this we also check to make sure the names match, rents are the same, end of lease is consistent. It seems very tedious but the process can be sped up by taking a holistic look at rent rolls, leases, and actual bank statements. Experience also comes into play (a few mistakes written in figurative blood) on what to look out for as inconsistencies. For example, a greatly increasing occupancy from 85% to 92% in the last six months might mean that the sell put in warm bodies into the property to get over the 90% occupancy mark, so we would audit those leases to see if they were properly screened. Its a lot of data, but this stuff isint rocket science.

While we are able with the review financials with the second set of eyes of our property management team, we recognize that we do not have the facility technician expertise of a HVAC tradesman, despite myself being a Facility Engineer for a medial office and building for the Federal Government for a short stent before jumping ship to work for myself. We hire third party inspectors who are the facility system experts to come on site to review all the major systems. Think of it as your property inspector for your house but without all the nonsense that the inspector says they are not an expert in home component XYZ. We get true experts, if they were not not they would not be commercial vendors… they would be a dude inspecting residential houses with an ipad and a ladder. We typically make sure we bring in the following outside inspectors: a roofing company to check/validate condition of the roof; an HVAC specialist to inspect a large sample size of A/C units to give us an overall condition report. If needed we also pay plumbers, who put cameras down main lines at each building; foundation experts to review soil content and inspect any previous/potential building shifting (we have been burned and learned from this and now it is a standard operating procedure); pool company to check on pool/equipment; and an IT audit to review all computer equipment onsite.

If the scope of work is over the capability of our property management team, we will get General Contractors to start refining the intended scope of work–and getting bids on that work to get hard numbers.

As you can imagine, a lot of things are going on between getting a property under contract, putting the word out to investors, and finally closing. We try to underwrite with more conservative numbers and often times projections improve the week before closing.

Actuals vs. Projected – which to use in underwriting?

The actual income and expense numbers the seller provides you for your underwriting should be close to reality, but even if they are, you’ll operate the property differently. Your numbers will be different and it will likely be calculated differently for example the old seller might account for the maintenance and repairs differently and not capex or they might stuff additional salaries or under report salaries of staff. This where the art to apartment investing comes into play and where we need to a lot of detective work to come up with a reasonable proforma that we can run the asset at. Luckily, we have past experience and many of our own assets to benchmark with and we also independently use our property managers experience and total protfolio insight too. We really like it when our property manager gives us operating budget proforma lower than ours because this is a good sign that we will beat our projections.

Now do you use trailing 12 month financials or from the last three months (T12 or T3)? Remember that the purpose of your underwriting is to project a picture of the future as accurately as possible. If the property had high vacancy for the six month period up to six months ago, then got units renovated, new marketing , or something else improved, and filled those units, it could be safe to say that the next 12 months of rent income will be more like the last three than the six months starting a year ago. So T3 for income. This is where the detective work goes on where you request information from the seller, broker, and look for other signs to verify the “story”.

You start at the big expenses very carefully – insurance, property tax, and repairs. Other big expenses like utilities and property management are easier to project.

Insurance – Some could be $225/door, others $300+. Nothing beats having real quotes from insurance brokers who you have had a working relationship with.

Property tax – this can be very hard to confirm. Will it go up when the sale is recorded? Or three years later? What is the county’s formula for calculating property tax? Go to the assessor’s web site, call the county, and talk to the broker. Experienced brokers know how it’s calculated and when it goes up. We usually account for a blanket increase in the coming years which can be as high as two times current, especially in aggressive tax states (to fuel growth) like Texas.

Repairs – These are sent to buyers and include other things in repair costs, like capital improvements. If an owner is upgrading a unit from laminate countertops to granite, that is not a repair, that is a capital improvement. They didn’t have to do that, they chose to so the unit would look nicer. But they are operators not accountants and in our cases not the most sophisticated at keeping good records. In many cases expenses got thrown into the same bucket as leaky faucet repair and plugged toilets. Look for repair expenses and be sure to include supplies, maintenance, and turnover expenses. They are often broken out separately but for you to decide if they make sense, lump them together. Rule of thumb might be $300-$600/unit but if it’s higher, do a property tour and see for yourself. Is it a very nice property? Then why so much on repairs? Or is the repair expense very low? Does the owner do repairs him or herself? So are they not accounting for his time and expenses? These are question that the GP digs for but as a LP this is just food for thought.

Utilities – there will probably not be much opportunity to tweak these because it normally is what it is. Implementing RUBS or a partial bill back utility program will require some time to implement and some will move out.

Management – if the owner has one or two people on staff and their payroll is reasonable, it might be a good plan to keep those people at take over. The property could be significantly overstaffed or there could be some staff costs hidden off the books. PM cost greatly range based on property size from 3% for larger properties to 8% for properties under 50 units. This is where we work with our property manager to create a scope and fee estimate and plug the number into our projections.

Marketing – if the seller’s numbers are $0, that might be a good indicator that they get drive by traffic or the free listings work for them. We plan on using marketing to get the optimal amount of traffic to be able to have amble tenant pool to select from and eventually build a waitlist which is why we can be pre-leased over 103%.

Landscaping, pest control – these aren’t huge percentages of expenses. It accounts for yard maintenance, snow remove, trees and bushes to trim, ponds, or storm runoff issues.

Check Your Numbers

Rent-to-value ratio: Should be 1.0-1.5% for class B and C multifamily housing

Cap Rate: – Estimate an exit cap rate of 0.5-1.0% higher than current prevailing market cap rate for similar class properties in the market/submarket (NOT the subject property’s cap rate) to account for market changes.

Equity multiplier: Should 1.8-2x over 5 years, or at least 80% return in 5 years. But the equity multiplier is just a quick way at looking at the total return. You need to check the other assumptions of the underwriting to make sure this Equity multiplier isn’t just wishful thinking.

Cash Flow: 5-8% cash flow a year is about average for stabilized assets

Purchase Price: In a light value-add deal, should be $55k-85k per unit in purchase price.

Acquisition or Organizational Fee: This fee is usually a small percentage of the purchase price of the property (typically 1-3%).

Asset Management Fee: To reimburse the sponsor for actively managing the property (typically 1-3% of revenues (gross rents))

Equity or Equity Placement Fee: Paid to an internal or external team for raising funds (typically 0-3%). This is tricky… lump this into the acquisition fee which should but 0-3% altogether.

Disposition Fee: This is the fee for the work involved when selling the property (typically around 1-3%).

Financing or Loan Fee: This can be 0.5-1%. This is tricky… lump this into the acquisition fee.

Construction Fee: If there’s a significant amount of renovation or development there may be a fee charged for overseeing the construction (typically 3-6% of hard construction costs).

Expense Amount: $4k per unit is normal for a stabilized property. I think this should just be included in the asset management fee.