3) Passive Investor Due-Dilligence Part 1: People

Vetting the GP

The General Partner or GP is the party that puts together and operates the deal. There are a lot of terms out there that pretty much mean the same thing such as sponsor, co-sponsor, lead, syndicator, operator, or deal sponsor so as we progress we will use these terms interchangeably.

Make note of the 3 P’s: people, process, & performance which we will be used as a framework to making an evaluation of the sponsor.

Documents to be aware of (however it may not be appropriate if you want to follow good LP etiquette especially as an invest under 5-10M net worth):

Most time is through some random sponsor who can't raise their own money on some crowdfunding website or some random cold email pitch and then I say, "No thank you, let me know how it goes."

The independent auditor’s report is critically important, as it will reconcile assets, portfolio balances, performances, and often provide insights on portfolio construction, liquidity of underlying assets, and back-office protocols. (Appropriate for larger institutional funds)

This allows us to see more detail on the portfolio from the time of last audit and allows us to reconcile the audit with the actual portfolio. If anything doesn’t line up with the audit, it only means that either we or the auditor are missing out on some information. (Appropriate for larger institutional funds)

They will all obviously be glowing references, but the choice of references can be very important. Make note of how the reference is connected to the sponsor.

Note: It may not be appropriate for an investor to ask for references. Think about it, the sponsor does not know you and may not want to give up past investors for their privacy. If your net worth is over 5-10M then it might be fair game to ask.

Make note of the service provider (e.g., property management, third party accounting firm, syndication lawyer), and perform due diligence on the service providers to get an understanding of the terms and length of the relationship. If you could see the same names come up again and again in different deals, then this is a good sign.

This gives us a sense of how the sponsor measures risk, what risks they control for, and how they fall within those parameters. (Appropriate for larger institutional funds)

This is more of a confirmatory information, but can also show critical piece of information such as assets under management as of a particular date, key principals, number and type of clients, and compliance with the law. (Appropriate for larger institutional funds)

This gives us a sense of the quality of communication, investment ideas, research, and insight into the manager’s personality and approach. Investor reports need to keep investors abreast of the happenings of the project but there is a fine line in giving too much information.

Do you tell your boss every little issue you are working through throughout your day?

People First

We tend to put a lot of emphasis on the numbers and checking of deal assumptions like reversion cap rates, full occupancy assumptions, and annual rent escalators because numbers do not lie. People do!

But in the larger picture, who you invest with is half of your due diligence. We will get to the numbers in the next module.

Below are some steps to perform due diligence on who you are investing with. Note: Some steps apply beyond passive investor LP syndication due diligence for an investment into something like a 300-unit syndication deal. For example, it may apply as well to situations where you would like to perform due diligence in order to invest with the operator as a general partner in the deal, or if you are considering a single family home debt investment (e.g., performing notes).

Spend Some Time on The Sponsor’s Website

A deal-maker’s site should be clean and well-designed, contain quality information, and be easy to navigate. You should, for example, be able to quickly locate the photos and bios of team members. The bios should be complete and updated detailing their experience with the projects.

Now, yes, I realize that websites can be deceptive and manipulative and can whitewash some very bad companies to the point where they look awesome. (think Theranos and Bernie Madoff, etc.). However, when you insert the art of reviewing websites into the rest of the protocol, you’ll see that doing so will give you some useful information.

In short: the site should evoke professionalism and reflect the quality of the deal sponsor and his or her team. You should get a sense of their level of commitment to excellence and to the success of their investors. Remember, we are looking for exceptions that stick out.

Review Their Marketing Material

Similar to your review of the sponsor’s website, make sure you use the same process to review their marketing material, whether it be webinars, podcasts, or even their answers on websites like Quora.

Are they constantly pitching and excluding real information? And when they are asked a question, are they answering it in an insightful manner, or are they evading it like a politician?

Post 2019: It seems like everyone has podcast and can create a fake celebrity status!

Quick List of Red Flags:

- Sponsor does not have any background in business. They might be successful academic or W2 worker but that does not translate to entrepreneur. That said, a college education is not everything but it does show that an individual did stick around at least four years to accomplish a goal. I like to work with professionals and have at least a college education when picking partners – a fire-breathing entrepreneur only gets you so far.

- Do they have a flawless or litigation free past? Beware of clean pasts! We want to see how they handled problems and made it through. Its not possible to have a flawless record.

- They are not a professional in the definition of the word where they are full time. And this is on the side of an IT job or engineering gig. I’m all for people going after their dreams but not with my money.

- Is this a team of good digital marketers appearing to be institutional operators?

- What is their net worth? I never liked with anyone who was not over $1M net worth. This is why I never liked doing BRRRs because primarily the folks you would work with are lower net worth team members who would be tempted to steal money because it’s worth a lot to them.

My Experience Starting in Syndications

At the end of the day, the number analysis (what assumptions were used) is only 1/2 of the battle in vetting a deal to invest in. The first is people. Never work with anyone you don’t know, like, or trust. That is how I lost $40,000 in my first LP deal.

Whenever I get a pitch-deck, I usually know if I’m going to invest in it even before I run the numbers because I know the people, I know them personally and we have a relationship outside of real estate.

People in our Family Office Ohana Mastermind bring me deals all the time but if it’s a cold contact I always ask “who the heck is this guy/gal?”

Typically, the answer is they found it on some sales page funnel, internet forum, or worse got it from a cold emailed out. Sophisticated investors call these “daisy-chain deals”.

I’ve listened to so many sponsors be “super excited” to pitch their deals.

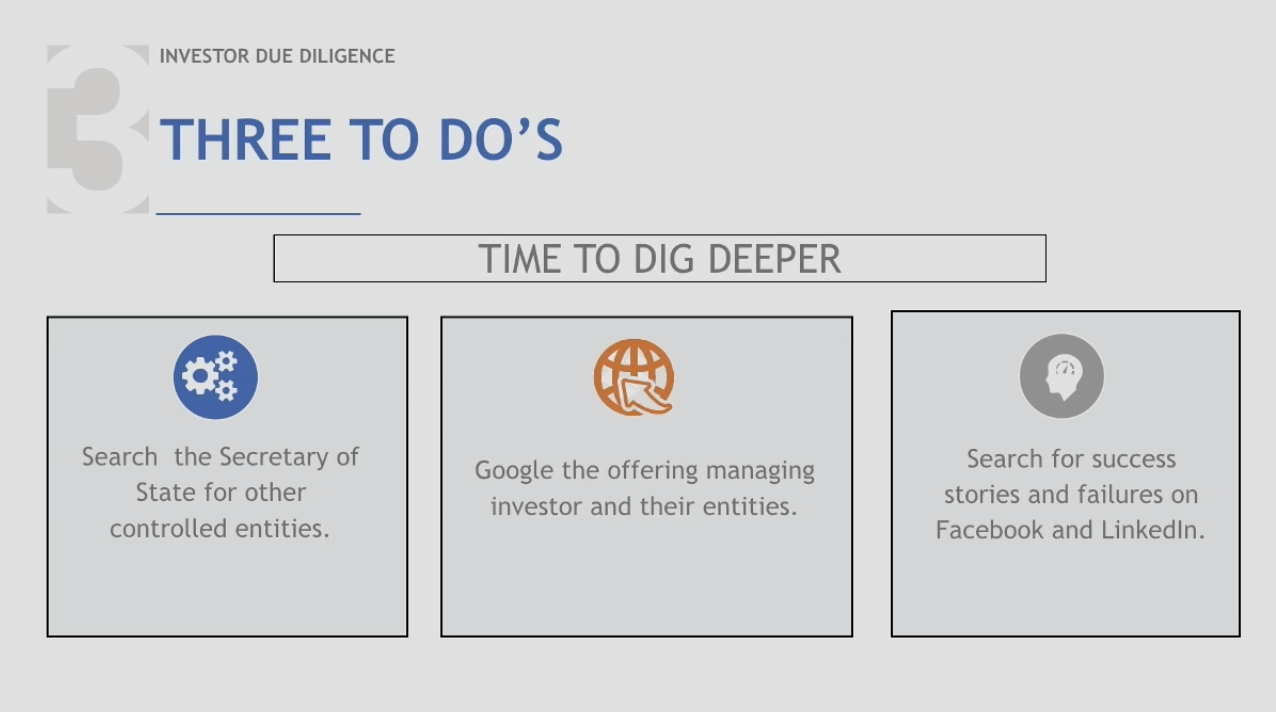

It sounds basic, but I Google stalk them and find them on Facebook and LinkedIn. In this day and age, if someone does not have a digital footprint that is their authentic self I don’t want to work with them — plus I want to work with real people, not robots. Ultimately, what I am doing is trying to see if any trusted person in my network knows the operator.

Real estate is all marketing, whether it’s a $500,000 primary residence or a $20M syndication. I was at a family office consultation and an institutional firm sent a consultant to represent them as investor relations. As I was doing my due diligence on him and the firm, I found that he was also previously in investor relations for another firm in another asset class on top of being just a run of the mill life coach. It’s unfortunate that in this world brown shoes, blue pants, and grey hair is looking the part.

#BluePantsBrownShoes

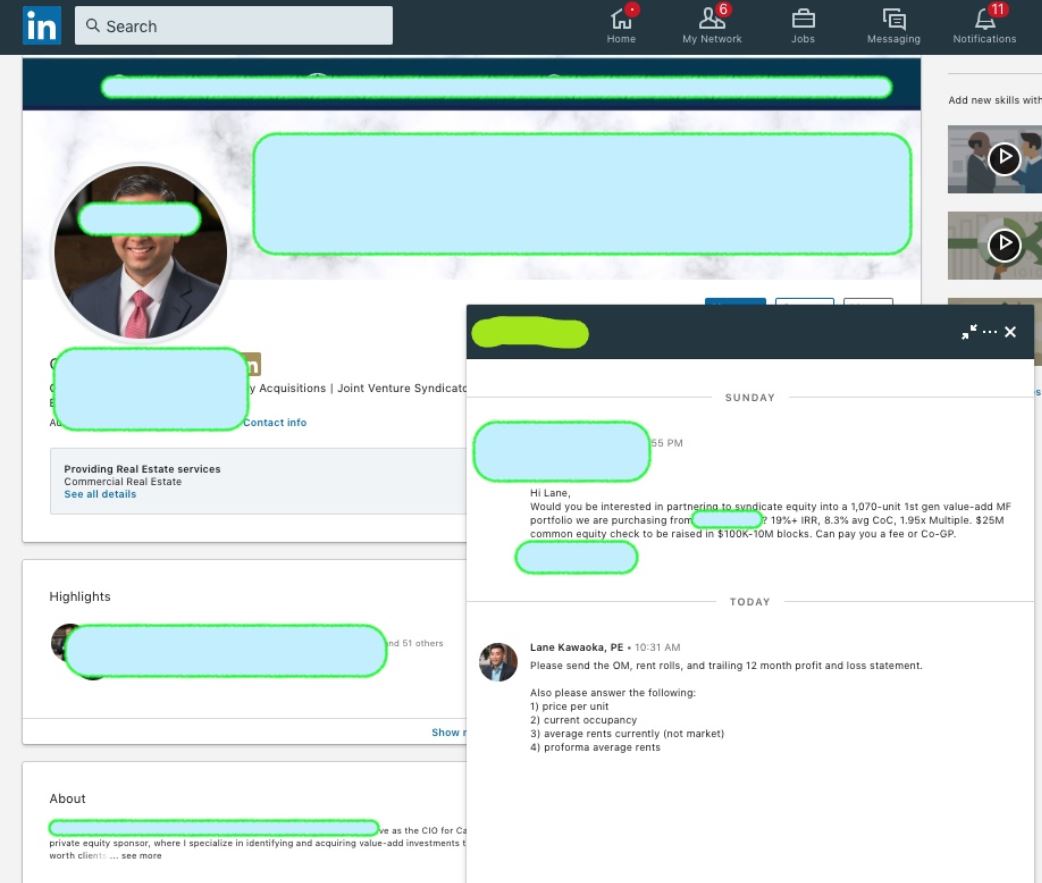

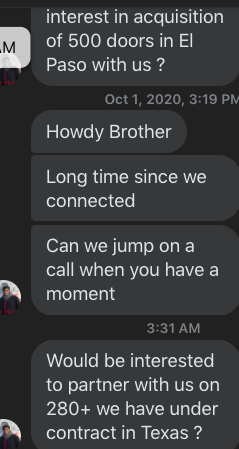

Another random cold pitch above. It is very rare that these COLD pitches ever lead somewhere. Most times it is just a waste of time. Everyone can create a nice logo, website, and take a pretty profile picture. Check out these past deal webinars so you are not taken as a syndication virgin who has never seen a deal.

To edge into why social proof and fake influence metrics are sought, here is some insight from global marketing consultant and author of the Marketing Rebellion, Mark Schaefer :

“Whether we are online or offline, we use social proof every day to make low-risk decisions when we don’t have the whole story. Our behaviour is often driven by the assumption that people with lots of followers may possess more knowledge about what is correct, popular, or ideal — a herd mentality”

” People just don’t dig deeper to see if somebody is legitimate or a list of followers is real so it’s possible to be rewarded for simply faking it. And many do. While badges of social proof can be gamed, humanity cannot. Nurturing true authority through authenticity, meaningful content, and an engaged group of followers will lead to a legitimate reputation and business.”

Again, as I am looking up their profiles, I am searching for common connections who I can ping and get more information. This is where it is critical to build real relationships where it spans to more than real estate. Here are some tips for that. In addition the Family Office Ohana Mastermind should be a great start for that.

Your network is your net worth and it is uber-important once you cross over a net worth of over $500,000 and start to become a more passive investor.

Other things to be mindful about are: be wary of whether this is a “student & celebrity” sponsorship team where the student is doing a deal (something you don’t want) and the celebrity is taking a big part of the General Partnership (20-50%+) equity in return for lending their profile picture/credentials with little in the day-to-day management. This leaves very little to the poor GPs who are actually doing all the work.

As a new passive investor, you are likely to be presented a bunch of junk as you are just connecting with the good marketers in the business first. The goal is to make organic and strong relationships with other pure passive investors and see what they are investing in.

I repeat for emphasis… Real estate is a people business. It is not like buying a stock where you can purchase it from any brokerage. You cannot apply some fancy AI or algorithm. You have to create a network to vet out good operators. You are investing in non-commodity investments where no two are alike.

Some Things I Learned Along the Way

Numbers are a big part of these deals and if you find the right deal, any half idiot can do okay (like my Atlanta deal where we more than 2x investors’ money in 2.5 years). If you want to grab the P&Ls and rent rolls, I’ll run the deal for you and see how the numbers really work. Numbers don’t lie, people do.

Remote Operator

I had a Rule where I would not invest in a deal where the main operator was living in Hawaii/California and buying a property in Texas. At the very least it needed to be a short 1 hour flight or less. More leniency will be given if the operator passes the other rules listed.

Types of Investors

Initially, I liked investing with professionals who got paid a six figure salary because indicates that they were able to execute on a plan to achieve a college level degree (showing commitment and execution) and hopefully (relying on social proof) can hold down a high responsibility job. After leading union based construction crews and over 250M of horizontal construction projects, it makes me laugh how people outside the realm of the contractor world can expect to effectively managing this type of staff. It does not take much technical knowledge of construction. I see some operators who have made the transition smoothly but many do not.

Is this a Side Gig?

I am all for people going after their dreams but they are not going to use my 50k to get started and build a track record or screw it up. I’ll be damned if they are 80/20-ing their time and attention at their day job and managing my money. Today, I only will work with full time operators. After leaving my day job, I know first hand what it takes to commit to a lifestyle and what happens when you “burn the boats”.

Track Record

You might trust someone but try to find someone who has actually invested with them before and gotten a good experience with them. Again, trying to find at least a couple past project that are at least going well. Don’t be that first sucker! Let it go to friends, family, and fools!

One of my favorite stories on managing due diligence came from a well-known investor who passed on a hedge fund because of a raincoat. Here’s the story:

The investor wanted to get to know the manager better, so they agreed to go on a hike. Halfway up the mountain it began to downpour. Unfortunately, the manager hadn’t checked the forecast and spent the latter part of the hike completely drenched. The (dry) investor realized at that point that the manager was a little too focused on the adventure ahead of him and not at all focused on managing the predictable risks along the way. The investor passed due to concerns over risk management.

We haven’t passed on any managers over rain gear, but I think the point is relevant. In poker, you must observe everything about a player: betting patterns, style of play, tolerance for risk, and personality. You piece together an understanding of the person from the data in order to get a sense of their tendencies. The same applies to due diligence on people. Fortunately, we have a lot more data to work with than at a poker table.

How to Check a Company

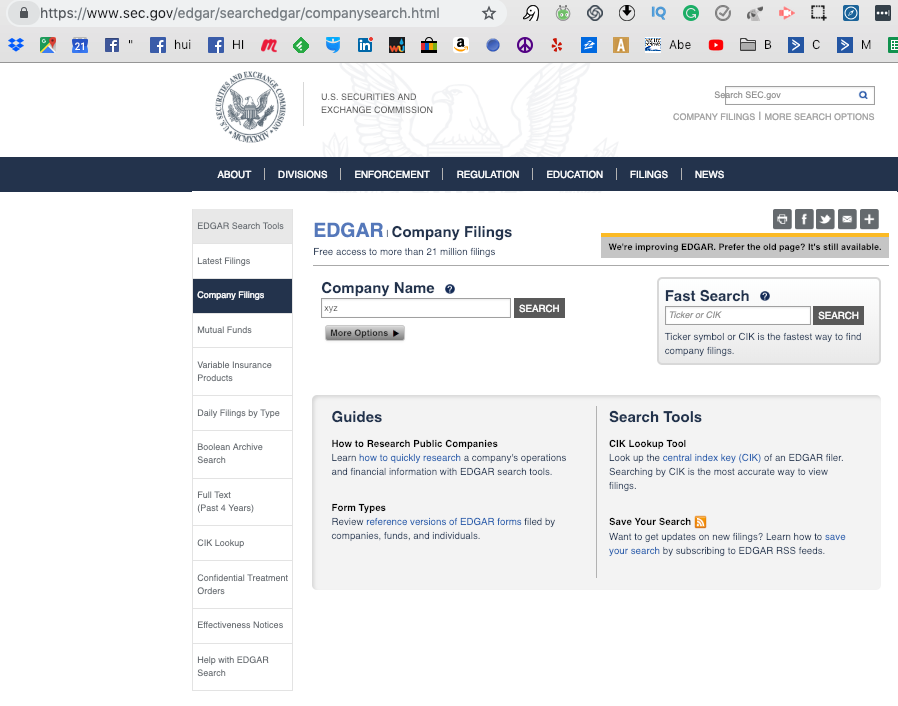

One “must” go to the SEC website (called EDGAR – I don’t know what it means, but I can assure you the government spent a lot of money for it).

You are looking for a form D for the deal. Query the LLC name…

Then you can read the docs here…

Background Checks

How to check a broker (regulatory check): BrokerCheck: Research Brokers & Investment Advisers

Skin in the Game

Also worth noting is that it’s incredibly important to know that the manager has invested in their own fund, and that they are risking their assets alongside yours. Most investors want to know what percentage of the manager’s liquid net worth is in the fund, and will often request documents to prove it.

Process: Operational and Investment

Now that you understand more about the people you’re working with, you want to understand the structure and processes that constrain them.

I know what you are thinking—operations are boring. The sexy stuff is how people come up with their brilliant investment ideas. Unfortunately, the operations and business side of the fund are not trivial matters. Research has shown that over half of all hedge fund blow-ups occur due to operational issues that have nothing to do with the investment process. As unappealing as it is to try to figure out the nuances of how Net Asset Value is calculated and reconciled with the fund administrator, it’s even less appealing to lose a billion dollars because you didn’t take the time. (Yes, turning over every stone means turning over the ugly ones too.)

I’ve seen institutional investors pass on funds for reasons which may not be immediately obvious problems to a new fund investor. This is again why I personally not like to invest in funds or blind pools where I cannot vet the individual asset that we are buying. In order words, I like single asset deals where I know what I am investing in so I can preform my own due-diligence on the the asset after I have done my due-diligence on the sponsor. Blind pool funds and funds are really hard to determine what is going on from a financial stand point. Finally, I have seen some sponsors throw their junk deals into a blind pool fund and serve up to unsophisticated investors looking for diversification. Think of it as the investment world of a hot dog!

Below are some examples. If you can think through the issues or potential issues with each real-life scenario below, then you are off to a good start:

-

A small fund required a single signatory on cash transfers.

Like any other business, embezzlement can be a problem for hedge funds. Requiring a single signatory to move cash, particularly for a small fund, means that a founder/key employee can potentially loot the place without limits. It’s not unheard of for a business owner to get served divorce papers, then decide it's time for an early retirement in a tropical, non-extradition friendly country. On a less major scale, an employee may embezzle smaller amounts systematically over time. Hedge funds generally have much higher asset liquidity than traditional businesses, and therefore cash stewardship is of utmost importance. For these reasons, institutions usually require double signatories on cash transfers, often with one signatory being a credible, independent fund administrator.

-

A fund had legal entities for their marketing, deal sourcing, and investment divisions of the firm.

Separate legal entities are put in place to limit liability (and potential transparency) between entities. Whenever a manager puts legal shields in place between different operational aspects of a fund, the investor should have a very clear understanding of why that is the case. In this case the reasons didn’t pass the smell test, and were likely in place to obscure important information for investors.

-

A large, well-known fund had used a Big-4 accounting firm as their auditor since inception, and worked with several offices of the firm over the course of their relationship.

Accountants understand the concept of multiple legal entities all too well. For example, each office of PWC may have its own separate legal entity which protects the greater organization and other offices from shared liability. In other words, working with 3 different offices of the same firm can be like working with 3 completely different firms. Another fact about accountants: If they find a problem with a fund (or a company), they will often resign rather than report their suspicions. In this particular example, 3 offices of the same accounting firm resigned over the course of the life of the fund. Unfortunately, most investors just thought: "Well, the manager has used a credible firm since inception, therefore it’s all kosher." Wrong.

-

The same fund in the previous scenario above, managed their fund administration internally.

Approximately 90% of all hedge fund frauds would be eliminated through use of a credible outside fund administrator to manage valuation, NAV reporting, subscriptions/redemptions, and the back-office functions of a hedge fund. Bernie Madoff in-sourced his administration. He couldn’t have reasonably pulled off his fraud had he used a credible outside administrator.

-

A fund was down 3% one month.

This by itself isn’t a problem. Some funds have high volatility and +/- 5% or more in a month isn’t unusual. The problem was that this particular fund’s investment strategy was expected to generate a slow, consistent half percent a month. A drawdown in one month of 3% in the context of that strategy was a red flag. The next month, the fund was down 9% and subsequently lost another 20% before shutting down.

-

A fund had rehypothecation agreements in place with their Prime Broker, a major, well-respected Wall St. bank.

Rehypothecation is when the fund lends their securities to their prime broker. The broker can then use the securities as collateral to lend against, and will generally pay the fund a small fee in return, which helps lower the fund’s brokerage expenses. Here’s the bottom line: When Lehman Brothers went bankrupt, this small distinction determined who 'owned' the assets. It was the difference between blow-up or solvency for many funds. (Literally billions were lost or saved over this nuanced operational detail.)

Performance

On every disclaimer on every document you will read from a hedge fund it will say: “Past performance is not indicative of future results.” I’m generally not a fan of legalese, but this bit should be taken as gospel. Historical returns are in the past, and without understanding them in the context of the strategy, the risks taken, and the changing nature of the strategy in the market, then those returns are meaningless. Statistics lie. At the very least they can mislead: Did you know that the Vatican City has 5.9 Popes per square mile? True fact.

Let’s go through another quick example. If a manager tells you: “we returned 100% last year.” Are you:

(a) Excited 😀

(b) Interested 🤔

(c) Skeptical/unsure 🤨

(d) Overwhelmed by feelings of inferiority over your own lousy returns 🤕

If the answer is anything other than lots of ‘c’ with a little bit of ‘b’ then you need to learn more about what performance means. (If your answer is ‘d’ I suggest yoga.)

Performance needs to be understood in context. What risks did you take to make 100%? What is the volatility an investor can expect on those kinds of returns? (No matter how great your returns are, you only need to lose 100% once to wipe it all out.) Statistics like Sharpe ratios, maximum drawdown, correlation, and volatility can only really be helpful in the context of the market and the strategy that contributed to that performance.

I once met with a manager who returned 142% in 2009 and 55% in 2010. Those were eye-popping returns, and they had all the right service providers and statistical ratios to “prove” how credible and great they were.

The manager told me that their whole strategy was to analyze momentum price signals, because “when you focus on one thing all day you get pretty good at it.” They were a complete black box as far as their model and their investment process, but the manager shared one aspect of the model: “When the market goes up we are able to capture those returns, but as soon as the market starts to drop, the model shuts down in order to mitigate any losses.” Classic baloney. (Explanation: Unless you know whether the market will continue to go down or up you can’t determine when to turn the model on or off. He was basically implying that they could perfectly predict the direction of future price action in the market.)

I passed on the fund, and it literally blew up the next month. (To be fair, I didn’t realize it would blow up so soon, though I did know that it would inevitably blow up with those returns coupled with no credible explanation of how they produced them or why they would persist.) The moral is that it’s hard to find an edge and generate consistent returns, and historical performance (whether good or bad) has to be understood in full context.

Sponsor Creep: This is where a sponsor builds up a good investor base and starts to increase fee structure, GP splits, and worse starts underwriting more aggressively to make the proforma look better than it is.

Question: Is a Sponsor/GP/Syndicator the operator or just raising capital?

Some investors want to work directly with the operator but there are some issues with that one being that the operator is obviously going to be biases to their asset class and particular deals.

Whereas a syndicator can be less biased. In a way they act as a non-captive broker like how we work with clients to get them the best infinite banking policy regardless of if its with Penn Mutual, Ameritas, Mass Mutual, Guardian. In this world however, a broker without a license like a Series 7 is a big no-no in terms of SEC securities laws and even then fiduciary responsibility is a laughable topic. The downside of a syndicator is that they just work with those unproven operators who just pays them the highest bounty (illegal if non a broker dealer) for capital raised. Think about this, if there is a good operator then they probably have a lot of investors and don’t need to pay a pop-up syndicator. The other side of the coin is if the syndicator is well connected and has high ethics they can provide a insiders point of view on the deals and be that unbiased source for diversified deal flow so the LP can actually have a life and enjoy their money and not be a professional investor (spending more than 10 hours a month hunting deals and people to work with).

Said in another way, some syndicators are mostly in the middle-person role of sorts; partnering with others who do the primary LOI/PSA/operation roles. Some on them will do their owe due-diligence on each deal and don’t rubber stamp the primary operator. That additional review layer definitely can add value in oversight and deal selection. A fee well spent for some types of investors.

Crowdfunding websites are an example of a “broker” where they go out find deals but they apply a hidden fee level to market the deal to the investors that they have found often these crowdfunding website opportunities have been watered down to go out to the unsophisticated “retail” investors who are very lazy, have zero peer networks. and just want to go to a crowdfunding website… very similar to 99.9% of people going to the 401k mutual fund options. At one time we looked at using a crowdfunding website to fund our deals and did not like the high fees and thought that having investors at $1,000-10,000 minimums was not going to be worth it due to the headaches that are typical of lower minimum investors.

Back to the question at hand, should you work with the operator or the sales-guy…. I mean syndicator/capital raiser?

The hard part is that its really freaking tough to tell… and without a Community like our FOOM and strong relationships that go deeper than a 20 min phone call or a beer or two with another peer Accredited investor its like operating in the dark. This was myself in 2013-2017 when I had to quite frankly kiss a few frogs. There are a lot of educational guru programs our there that pay $30-50k and the content tells you to make it as a new operator/syndicator is to take a lot of selfies to put on social media and fake it till you make it. Everyone (newbies with under 500 million in assets to 5B AUM firms present themselves as quite successful, established with experience and connections).

Sometimes these groups will offer Mentorship/Coaching on how to be a GP. From my experience, only 2-4% of those who pay that exorbitant fee actually break through after 2 years of grinding (faking it till they make it and some broker gives them a halfway decent deal – or they force through 99% of deals that are crap). The way the education business works is that the 98-96% of those who did the program give up and because investors to those unproven students in the program – funny huh!

Personally, I want to work with someone operator or syndicator who is a decision maker in the GP and holds no less than 25% of the GP voting rights. There are a myriad of deals out there, typically by newer guys who have 8-20 GPs. Most of which are on the team to just bring in 500k-1M of investor LP capital in. This is a huge red flag in terms of SEC securities law. And I see this as a potential issue for LPs with so many GPs or cooks in the kitchen with some motivations not purely aligned with what is best for the LP. In my earlier deals, it was really frustrating to get anything done and it was detrimental to the asset. But those days are mostly over because you folks come in with the Hui and we come in with as much as 10-12M into one deal and collectively control majority of the voting rights. This is important because on my one bad deal where we had a dishonest and incompetent GP our group was able to quickly vote them out and I was able to control the GP on behalf of my LPs.

I have mentioned earlier that once a firm gets over 500M or 1B in assets under ownership they are to a certain level of sophistication where they have shed their newbie status and an LP might not need to see 10%+ of the GP skin in the game. Highly reputable first don’t put any skin in the game as a data point, yet you see these stubborn LPs don’t look at the whole picture. But anyway… some syndicators might fudge their assets under management/ownership even thought they only brought in 250k or 1M in a 50M deal where 15M of required capital was needed (less 6% of the equity) yet they count the score as 50M of AUM. So its tricky… and everybody does it but the question is on all these deals on your so-called track record sheet how much GP% stake did you have. Today, as of early 2022, we have funded over 150M in equity from our Hui group alone. That is a fraction of these venture capital powered crowdfunding websites and often 10-20x our competitors taking selfies on social media or 2-3x those who are actually running legit operators.

Questions to Ask the Sponsor

Because private investments are passive and investors will have no hand in management, the most vital step in the whole process is scrutinizing the managers, their experience, and track record. You can find the complete list in our Due-Diligence Scorecard & Checklist.

Here are some questions to ask:

– How long has the sponsor team been in place?

– How long have the principals been in real estate investing?

– How many assets have they acquired or currently own, manage, etc.?

– Have they gone through an up-and-down cycle?

– Did they go through the Real Estate Crisis in 2008?

– How familiar are they with the property location?

– Have they ever had to make capital calls on past deals?

– Search LinkedIn and Facebook and contact mutual friends to get references

– What were the projected returns vs. actual performance?

– Can they explain their losses?

– How good are the deals? Risk/reward, target ROI, downside protection.

– What is the fund transparency? Will you show the assets and performance in the fund?

– What percentage of deals hitting the sponsor’s desk get reviewed (ideally less than 25%) and what percentage gets funded (ideally less than 10%)?

– Who are the major players on the team, what do they do themselves, and what do they outsource?

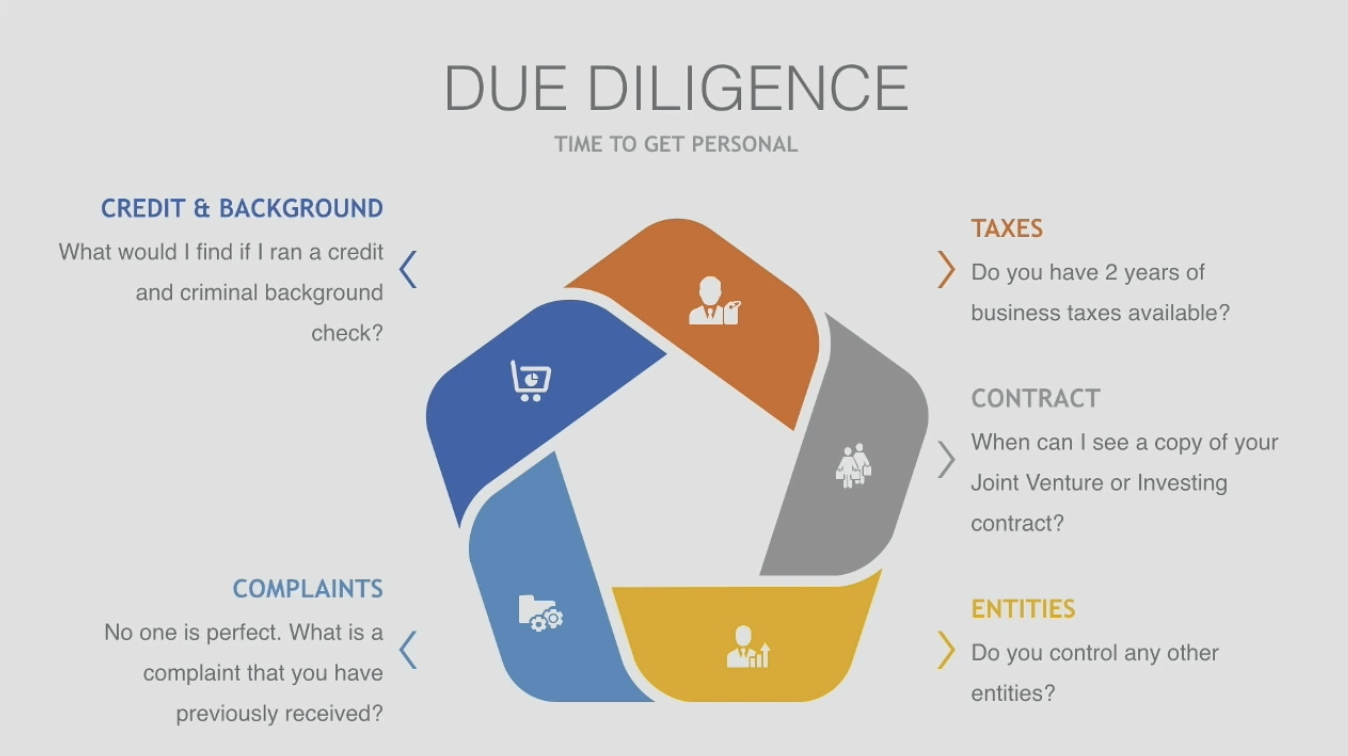

– Any criminal history or financial background issues that I should know about (including what I might find if running a background check?

– Are the GPs financing with their own cash reserve and net worth, or are they dependent on loan sponsors/key principals to qualify for debt? When the sponsors get loans, the lender requires that they have a certain net worth (e.g., equal to the loan amount) and cash reserves (10% of the loan amount).

– Do they have in-house property management or are they using outsourced professional property management?

- Does the property manager/management team have experience with similar projects in the market?

- Does the property manager have a stellar reputation in the industry and are respected by their peers?

- Are they committed to bringing value to the project (for example, in the case of multifamily, to create a great apartment community)?

- How likely is it that the property manager going to efficiently execute the project’s business plan?

- Is there a track record of solid, quantifiable success as a property manager?

- What type of education does the property manager have?

- Are the property manager’s skills being constantly improved and updated?

– What types of deals does the fund invest in? (Debt, equity, asset type, deal size, location, value-add or performing.)

I can’t say this enough. Even if your deal’s sponsor has done everything else perfectly, the wrong property manager or management company can cause an otherwise solid project to unravel. Spend some time making sure that the sponsor has the right person for the job.

Other Things to Look Out For

-

Money Going Hard

Many general partners put up substantial amount of money that is non-refundable after a certain point in the diligence phase. This is called your money going hard. It's a dirty little secret that many operators will force a deal to happen with loose underwriting rather than pull out of the deal and eat $50,000 to $200,000 of their non-refundable earnest money.

Capital Raisers

In the past couple years there is a new breed of sponsors that call themselves “capital raisers”. Many of whom are violating securities laws because they’re being paid transaction-based compensation, despite not having a broker-dealer license from FINRA. These capital raisers seem to be coming up with all kinds of creative “loopholes” around broker-dealer laws that just don’t hold up. Over the past few months, I’ve seen or heard about the following suspect practices:

- Capital raisers receiving compensation from the investment's acquisition or asset management fees

- Capital raisers getting a portion of the management or sponsor entity in proportion to how much they raise, this is also known as “Deferred equity structures”

- Having an excessive amount (over a dozen) of individuals in the sponsor team

- Capital raisers marketing to unsuspecting investors, claiming to be “part of the General Partnership”. NOTE: Do your due diligence, you can verify who's in the GP by checking the PPM or Investor Summary/Deck

Ok so how do I prevent me going into one of these questionable deals? Take a look at the entire GP sponsor team and ask what are the roles here. It is unusual to have more than 3-4 people in the sponsor team – anymore and they are likely capital raises for hire which are illegal. Its fine if they have a legit role but be wary. Remember our due-diligence is with the “operator” not the “marketer” of the deal.

- Commit. The lucrative world of private investments are not for the weak or flaky who are quick to change their mind. Most funds will require a commitment to a long-term vision of the management and investment windows of 3 to 7 years. Are you up to the task? If you like to jump from one investment to another… this isn’t for you.

- Communicate. Management should communicate with you regularly, so be sure you stay in touch from your side. Discuss with management any issue or problems you have.

- Be Humble. Don’t expect to know everything about everything. Trust the experts in their fields. If they know what they’re talking about, then it’s time to step back and let them get to work – that is if you are working with a proven team.

To avoid bad deals, ask the right questions, and do your due diligence. Don’t work with random people!

I constantly get pitched in some shameful ways like Facebook messenger and cold texts to bring our group into random deals with total strangers.

On the flipside, just because an operator has supposedly many successful full-cycle (exits) deals with high average returns, they might just be the lucky guy who invested in the right times and them changed their underwriting style or business plan.

Like beta and alpha in the stock market, returns include both a market component (largely out of the operator’s control) and an operating component (largely based on the acquisition terms plus the operator’s skill and resources). Those who depend on the market for their returns will be at the mercy of the market when things go south.

Ironically, it’s likely that a true professional (i.e., seasoned, tenured) operator’s returns may not be as high as some big-name, newer operators in rising markets. Some of these less seasoned name brands have taken major risks (using extreme leverage or short-term debt, for example) that have paid off in a rising market.

But let’s see where these risks could land them when the market turns against them. Investor equity in high-leverage deals can evaporate when just a few things go wrong. We watched this happen to too many investors in previous cycles like 2008 and before.

The projected and past returns should always be evaluated in light of the risks including…

- The operator’s experience, team, and operating capabilities

- The type of debt, the term, loan-to-cost, and DSCR

- The acquisition price and value-add opportunities

- The underwriting assumptions (like occupancy, revenue growth, the exit cap rate, and much more)

- A sensitivity analysis considering ongoing interest rate hikes, deflation, higher vacancy, etc.

- The operator’s real financial skin in the game

- The barriers to entry around the property and/or asset class

It is tough for most investors to accurately account for all these items when evaluating an operator and an investment opportunity. It is challenging for us to do so, and this is our job with a lot of unfair networking positioning advantage on the average LP. The next section will help you understand some of the numbers behind this deal to increase the odds of achieving your investment goals.

Frequently asked due diligence questions

BELOW ARE LIMITED PARTNER INVESTORS’ QUESTIONS FROM PREVIOUS DEALS WITH SLIGHT CHANGES TO PRESERVE THEIR PRIVACY. THE SPECIFICS ARE BY NO MEANS TYPICAL, SINCE THEY ARE FROM A WIDE RANGE OF DEALS AND BY NO MEANS TYPICAL, HOWEVER IT ALLOWS INVESTORS TO GAIN INSIGHTS FROM FELLOW LIMITED PARTNER INVESTORS.

Management Team

Yes, we plan to invest alongside our fellow investors. We already have around $130K that the sponsor team has put into the deal (deposits, etc.) that is “hard” and committed. The sponsors will be at least 10% of the closing capital. The $1.3m is what we’re aiming to have total for closing, but our actual cash to close and raise is slightly lower (~$1.1-1.2m). This accounts for closing costs, fees, and to ensure we have the additional working capital to start. (Cash to close is lower because a lot of times the bank may not require all the Cap Ex money to be in the bank at the very start)

This is a great hybrid play with a proven model to increase rents in a strong market. The deal is “clean” and we can come in and do little and still cashflow.

It is only for sponsors who don’t take their comp up front. It’s a tax thing. (This term is present in some deals and not in others. It is mainly for tax use for the sponsors to get taxed accordingly. In our deals, equity is allocated per units which can be purchased to investors. For example in an 80% GP /20% LP deal there might be 800 units up for purchase and 200 units given to the GP as their carried interest in running the deal.)

This is called a cash or capital call. The cash reserves serve as a buffer for such an event. Often times, in order to “save face” additional cash is asked from the Key Principals of General Partners, but yes it is possible to have a cash call from LPs however unlikely.

That’s exactly why you do these deals. The investment goes through some vacancy but overall still cashflows until occupancy drops to 70%. This is where I would like to be in a downturn in the economy.

There are roles that we signed up for, however, it’s fluid and in the end all of our brands are on the line for the sake of the investment and team.

4 parts of a deal that shape a guideline on who gets what:

1) Who is bringing the funding

2) Who is doing the work

3) Who found the deal

4) Whose experience/network is being leveraged

A good starting point is evenly weighing those at 25% each but it’s very subjective.

These contacts are through the property manager, who manages the process with the different trades. We will still get other outside bids after closing to make sure we’re getting the best price/service.

We have other contacts in the area through other relationships and because the sponsor team already owns assets in this area as well.

Business Plan

Yes. There were no big surprises, other than some minor deferred maintenance that we are able to get a $25,000 credit for. Unit interiors need some repairs, but again nothing major. All of this has been accounted for in our underwriting.

We are oversubscribed meaning people have committed funds, but are in the process of signing docs and wiring in funds. There is still time to get in, but email me ASAP.

Likely Check. Checks are easier especially because people move around so much. But we can do ACH if the bank allows.

Not really, especially for such a small position. In my opinion, it does not happen and if you think you need the money back, do not invest and please save everyone the hassle. This is one of the reasons sponsors don’t typically bring in lower net worth individuals and non-accredited investors into these deals.

Rehab is done with natural turnover in order to optimize cashflow. In some investments there is a lot of vacancy which expedites rehab. However, there is a big hurt on cashflow during that period.

- The current owner previously bought the property out of foreclosure. Previously, it had not been taken care of, bad tenants, etc.

- There are older (3+ yr) bad reviews online from when it was run poorly prior (was bought out of foreclosure).

- Property also had an incident.

- Obviously, that hasn’t affected occupancy and performance at this point, but it gives us a fresh start, signals new ownership, and we can ride the wave of a new sheriff in town.

- Rebranding, as well as the new name, were suggestions from the property manager.

- Property next door rebranded and going through renovation, so we’re keeping suit.

- We’ll continue to look at with property management. Some immediate things I see are that the Townhome units have full W&D hookups, so we’ll look at opportunity there.

- The laundry income is underutilized.

- We’ll also look at turning the office (currently a 2BR) into an efficiency which property management thinks we could get $550/mo. for.

If the total raise was 1.3 million, your $30K investment is 2.3%. But since it’s an 80% LP / 20% GP split, you own 1.8%. But 1.8% of 114 units is 2.1 units.

100% return means if you invested $100K, if you added up your proceeds from cashflow paid quarterly and money from the sale/refi you would walk away with $100k and your original $100k.

The normal 5-year hold is because it takes two years to get all the rehab units done, two years to get the culture to change and further bump rents, and the final year to stabilize the books for the new buyer. Of course, this is a conservative projection.

All deals are pretty much paid up and financials are rolled up on a quarterly basis starting around the half year mark as we force bad tenants out and stabilize after takeover. It has to do with minimizing admin and being cost effective. This is the case for the Class B traditional equity. For Class A (debt) investors, we pay monthly and from the first month.

We could sell or refi earlier (year 3-4) or even after year 5-6. It is unlikely we would hold past 8-10 years. It’s based on how much returns we can squeeze out of the asset with the least amount of the risk. We monitor the market and try to make the best decision for everyone… this is why it is good to be aligned with a performance split with the sponsor.

Not on this one particular project. It acts like a debt investment – no depreciation. More for regular equity investors.

I might have made a general statement, but most investors follow a bit of progression where they start out looking for cashflow and then look for higher gains (no cashflow) but in the very endgame (or over 4-6M net worth) they just want a fixed return that the debt investment yields. Here is a short video in our new Mastermind Syndication secrets series coming out soon discussing this progression of an investor’s mindset. We look to cash out Class A investors as soon as we can refinance the property which will make Class B investors go up. We estimate this to happen 2-5 years from now.

Class A gets paid in the first month so it’s pretty instant feedback (again Class B investors are projected to wait a couple quarters and then should be paid on a quarterly basis). Class B gets the upside in the deal, so that is the tradeoff. Most investors will get the Class B unless they are higher net worth or really want cashflow.

A Class (debt investors) is more for conservative and very high net-worth investors. It’s a 10% return starting right away paid monthly, but no upside. Plus we try and cash out those investors out of the deal as soon as we can (2-4 years). Class B investors are traditional equity who have a split of the profits but will likely have to wait a couple quarters to start getting quarterly distributions.

We continue to cashflow. If we hold longer, we will refinance and basically pull all your initial investment so you are still cash flowing with none of your initial investment, so you are playing with house money at that point on.

Yes, the more money the property makes the more money you make. If we make just $25 more per unit it means huge dollars for us!!! You take 80% of all profits. When the property is really preforming well above a 14% IRR the GP takes 25% of profits and LPs take 75%.

- Payroll is the largest item here ($1500/door), the current property had an extra full-time maintenance person. Since Provence manages the property next door, we will share resources which will bring that down closer to industry standard (we’re underwriting $1200/door).

- Other things we’ll look at are utility savings with energy/water conservation.

Property/Location Details

No. Residents pay their own Electric and Water is billed back. Residents are also charged a Trash and Pest fee.

I have four of my rentals like within a few miles of this apartment. I don’t think any of mine are currently section 8, but I am a real fan of it. What you have to worry about is the LIDCA or LURA or LURK restrictions on rent. Sometimes they have credits to builders when they build these and that is a real pain to deal with if you are the best buyer. I have not met anyone who has specialized in repositioning these because you have to be really careful for the expiration date. It’s usually something brokers trick you into buying.

The exact percentage has been around 8% total Section 8. A handful of those are carryover from the previous owner and long-term residents (5+ yrs). The property currently doesn’t rely on it to maintain or attract tenants and not high enough for us, in general, to be too concerned outside of normal resident churn. One good thing is the property has actually been getting the current asking rent from the Section 8 residents. There are always some units not repositioned to leave some meat for the next buyer, so I’m sure naturally these will be it.

- All the flat units have these PTAC units with electric wall mounted heaters in rooms.

- One of those units was retrofitted with central HVAC.

- All the Townhome style have traditional central HVAC with indoor air handler and outdoor condensing unit.

- Kind of is what it is, we could try to convert the flat units but that probably wouldn’t be cost effective.

- Residents pay electric anyway.

Personally, I pay no attention to Sales comps. It’s something brokers always put in Offering Packages to fill space. These apartments are commercial assets and valued on NOI not SF, Units, or comps. As for the rents take a look at the graph in the webinar.

We are just doing a 7.8% increase. Anything over 15% is too high.

Their business plan was to take from 70% occupancy to this point.

The current seller has owned for about 2.5 years and has a shorter term business model when he buys properties. He is focused on large value-add with more legwork. He tends to get short-term variable financing, work on distressed properties, etc. He’s taken this particular property to this point and ready to take gains and move to next. He’s looking for new deals like us.

This is due diligence that you need to do on your own and check out City Data and crime websites. I have owned 4 properties in this side of Atlanta. It’s not the greatest area but definitely not the Southside (Along the Marta) which is where you do not want to be.

I am working on a scorecard as I’m getting a little (loose) on how I view these deals where it’s more off heuristics and seeing so many I know exactly what to look for. Which is terrible to communicate with others. I realize that “I just know” is not a good answer and so is “trust me” as it does not work with everyone. Plus, I’m always afraid that I will forget it, much like the motivation behind the podcast being to memorialize this.

Using the rubric of 50% operator and 50% deal…

- Property was bought out of foreclosure couple years ago for $26K/door but that seems kind of irrelevant. The property was purchased after the 2008 financial crisis at what we are paying today.

- Properties in area are trading for $50K/door

- Number of new apartments being built further northwest.

- Rent increases in that area and north are starting to drive people south.

- There’s a couple of different new townhome developments within a couple miles

- Path of progress so to speak.

- Current owner owns multiple properties in area and has been selling off assets.

- He has shorter term business model focused on large value-add projects with lot of legwork and getting short term financing on it.

- Taking gains and buying elsewhere. Bought property out of foreclosure from Fannie Mae.

- Brought occupancy back up (70%) and spent dollars on exteriors including paint, shutters, roofs, and stairs/decking.

- He also started own his property management company, so he’s doing different things.

- $44K medium income for submarket. Workforce/blue collar housing. People working in services sector, retail, public service, food service, etc.

- For this particular submarket, the major employers are the Emory conglomerate (University, Medical Center, Center of Disease control) and Dekalb County Gov and Schools (the county center is 5 min north).

We have the rent rolls and do an audit. We are looking for abnormalities, but everything so far looks like a typical hodgepodge. In the end it works its way out to be a wash because if you have a lot of vacancies in the beginning of ownership, it can be good cause you “rip the band-aid off quickly” and get a jump start on rehabs/end business plan. And if you have to wait 3-6 months for a bulk of the vacancies to come then you get better cashflow in the interim. With a large property like 300+ units, it dilutes the risk that you are considering here.